Tuesday, September 1, 2020 - Desert Plants

- Mary Reed

- Sep 2, 2020

- 16 min read

I walk by a home with a display of desert plants in its landscaping. These types of plants do fairly well in the Dallas climate which has an average rainfall per year of 36 inches. Dallas is not a true desert like Phoenix which only gets an average of 8 inches of rainfall per year. I once accompanied a friend on her business trip to Phoenix. While she was in meetings, I explored the city and visited the Desert Botanical Garden. It has more than 50,000 plant displays on 55 acres. There are thousands of species of cactus, trees and flowers. Seeing all the different shapes of cactus was an otherworldly experience. It really felt like I was on another planet.

I recently planted miniature cacti with red heads in the planter by my front door. They are very attractive and so far, require less watering than the flowers that were previously there. My only other experience with desert plants is eating nopales or cactus pads in Mexico. They are really quite tasty and available at some Mexican restaurants in Dallas.

Desert Flora – Wildflowers

Desert lily

According to the article “Desert Plants: Plants in the Desert Biome” at desertusa.com, the desert lily was called "Ajo or Garlic Lily" by the Spanish because of the bulb's flavor. Native Americans used the bulb as a food source. These bulbs can remain in the ground for several years, waiting for enough moisture to emerge.

The U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management administers the popular Desert Lily Sanctuary, officially designated by Congress in 1994 as part of the California Desert Protection Act, which reinforced BLM’s administrative protection of the area dating back to 1968. The sanctuary is located on California State Highway 177, just 7 miles northeast of Desert Center. The best time to visit the Desert Lily Sanctuary is February through April.

The plaque at the entrance to the sanctuary:

Tasker and Beula Edmiston first observed the desert lily on Easter Sunday 1957. The Edmistons worked tirelessly with the Bureau of Land Management to protect this outstanding natural area. On Easter Sunday 1968, this 2,000-acre site was selected for protection because of its spectacular floral values.

The Desert Lily prefers dry, sandy flats below 2,000 feet elevation. The plant's bulb may lie dormant underground for many years waiting for ideal conditions to bloom. In the wet spring months when the amount of moisture, sunlight and temperature are right, the stem sprouts from a bulb buried 18 to 24 inches underground. The mature plant may be several feet tall with a flower cluster at least a foot long. Each blossom is approximately two inches long. This magnificent flower presents a woundrous view.

These plants are found in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts of southeastern California, western Arizona and northwestern Mexico. Large, cream-colored, funnel-shaped flowers, 2-1/2 inches wide, bloom March through May. Flowers have six petal-like segments, each with a silver-green band on the back. A cluster of long, blue-green leaves with white margins grows just above the ground. The desert lily's leaves are about an inch wide with wavy edges and grow 8 to 20 inches long. All the information about desert lilies provided above is attributed to A.R. Royo.

Blue phacelia, wild heliotrope, scorpionweed

Blue Phacelia is an annual shrub of the waterleaf family or hydrophyllaceae. This species is known by other common names, including wild heliotrope and scorpionweed. It often grows up through other shrubs to a height of from one to three feet. Green, fine-haired, fernlike leaves and the coiled, scorpion tail arrangement of the flowers are characteristic of this species.

The more than 100 species of phacelias in the western U.S. are difficult to distinguish one from another except by seed identification. But the pale blue flowers and weak, straggling stems of the phacelia distinguish it from other desert phacelias.

It can be found in the Sonoran and Mojave deserts of southeastern California to southwestern Utah and south to Arizona and northwestern Mexico in washes, slopes and roadsides between 1,000 and 4,000 feet. The flowers are bell-shaped, pale blue flowers with five rounded, united petals and bloom February through June. Flowers are about 1/4 inch-wide, in finely haired, terminal coils.

California poppy Eschscholzia californica, a dicot, is an annual or perennial herb that is native to California and is also found outside of California but is confined to western North America. E. californica is named after Russian naturalist J.F. Eschscholtz, 1793–1831, and is the California state flower. Certain Indian tribes chewed the petals like chewing gum, and a potion made from the roots was used as a remedy for a toothache.

It is found in the Mojave Desert, California Floristic Province and east of Sierra Nevada in grassy, open areas at elevations from zero to 2,000 meters. The flowers are solitary on long stems, silky-textured, with four petals, each petal from two to six centimeters long and broad. The plant can be a perennial herb from a heavy taproot, erect or spreading, without hairs. It is sometimes covered with a waxy, whitish or bluish film that is easily rubbed off. It blooms from February through September and can grow to heights of two to 24 inches. The leaves are divided into three round lobed segments.

The Antelope Valley California Poppy Reserve is in northern Los Angeles County, California. At the peak of the blooming season, orange petals seem to cover all 1,745 acres of the reserve. Other prominent locations of California poppy meadows are in Bear Valley (California, Colusa County), Point Buchon and numerous other locations.

Desert sand verbena

Desert sand verbena or abronia villosa are sticky, hairy creepers that have flower stalks up to 10 inches long, with stems trailing up to three feet. Leaves are oval with wavy edges 1/2 to 1-1/2 inches long. Sand verbena can carpet desert washes for miles after abundant winter rains. It is found in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts of southeastern California, southern Nevada, western Arizona and northwest Mexico in sandy flats, dunes and desert roadsides below 1,500 feet.

The flowers are bright pink, trumpet-shaped, five-lobed, fragrant and two to three inches wide. They bloom February through May.

About the cactus

The cactus family is one of the most easily recognized plant families in the world. Their beautiful blossoms, thick stems and unusual shapes attract thousands of people to the desert each year. Cactus, as a plant family, show variations between the individual species. They range from the three-inch fishhook cactus nestled in a rock crevice to the towering saguaro cactus which reaches heights of 30 to 40 feet. Cactus grow on rocky hillsides, alluvial fans and in barren washes throughout the desert.

Cactus natural history

Cactus is an American plant family not native to Europe, Africa or Australia. Very little is known about early cactus plants because only two cactus fossils have ever been found. The oldest — found in Utah — dates to 50 million years ago and was similar to today's prickly pear.

Cactus plants probably grew in a tropical environment until about 65 million years ago when, in much of California, the climate changed from year-round rainfall to a pattern of dry summers and wet winters. Later, when the desert began to form as the Sierra Nevada and Peninsular Ranges rose and blocked rainfall to the eastern valleys, the cactus adapted to the dry, desert conditions.

Although cactus are synonymous with desert regions, they are found in some unlikely places. In the lush, tropical regions of Mexico, South America and some Caribbean Islands, tall columnar cactus grow among hanging vines and large-leaved trees. One species grows at an elevation of 11,000 feet in the Sierra Nevadas.

Cactus adaptations to the desert

Cactus owe their success in the desert to their structural adaptations. While other desert plants may have similar features such as spines and succulent stems, these evolutionary traits reach a zenith in the cactus.

Cactus take advantage of the lightest rainfall by having roots close to the soil surface. The water is quickly collected by the roots and stored in thick, expandable stems for the long summer drought. The fleshy stems of the barrel cactus are pleated like an accordion and shrink as moisture is used up. These pleats also channel water to the base of the plant during rain showers.

When water is no longer available in the summer, many desert shrubs drop their leaves and become dormant. Cactus continue to photosynthesize because they have fixed spines instead of leaves. The green stems produce the plant's food but lose less water than leaves because of their sunken pores and a waxy coating on the surface of the stem. The pores close during the head of the day and open at night to release a small amount of moisture.

The dense network of spines shades the stems, keeping them cooler than the surrounding air. Many barrel cactus lean to the south so that a minimum of body surface is exposed to the drying effect of the midday sun. Cactus pay a price for these water-saving adaptations — slow growth. Growth may be as little as 1/4 inch per year in the barrel cactus, and most young sprouts never reach maturity.

Uses of cactus

For many animals such as the bighorn sheep and the antelope ground squirrel, cactus are an important source of food and water. The cactus wren and California thrasher often build their nests in the buckhorn cholla. These birds trim spines from the cactus to permit their own easier access, but rely on the balance of the spines for protection from foxes, coyotes and predatory birds. The Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers chop burrows in the long arms of the saguaro cactus. Owls, flycatchers and starlings also use the abandoned homes in the saguaros as their abodes.

Different varieties of cactus were used for food and medicinal purposes by Native Americans for thousands of years. The Cahuilla Indians spent the cooler months gathering wanted plants. They harvested the fruit of the beavertail cactus for its sweetness. The fruit was cooked in a pit with hot stones for at least 12 hours, and the large seeds were ground into a mush. When the flesh pads were young, they were cut into small pieces, boiled and served as greens.

Native women used gathering sticks to harvest the buds of barrel cactus to prevent being injured by the sharp spines. Usually these buds were parboiled several times to remove the bitter flavor before they were eaten.

The buckhorn cholla cactus was used medicinally by the Cahuilla. The stems were burned, and the ashes were applied to cuts and burns to aid in the healing process.

Where to see cactus

Cactus are found throughout the desert regions and usually bloom in late March through May. The blossoms range in color from the deep magenta of the hedgehog cactus to the cream-colored blossoms of the saguaro, and from bright yellow prickly pear to the pink blooms of the beavertail cactus.

Some of the best locations in the United States for viewing cactus:

Arizona

- Saguaro National Park

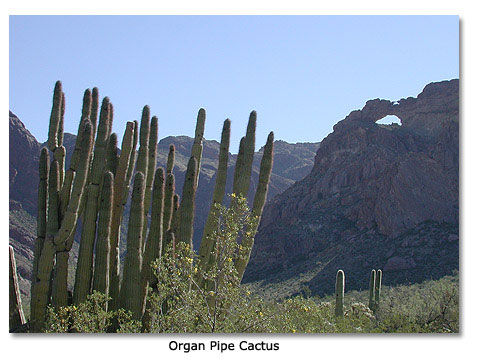

- Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

- Botanical Garden (Phoenix)

- Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum

- Apache Trail (Route 88)

California

- Anza-Borrego Desert State Park

- Joshua Tree National Park

- Death Valley National Park

- The Living Desert Museum and Botanical Park

Texas, Southern New Mexico and Mexico

- Chihuahuan Desert

Protection

Cactus — highly adapted to the harsh desert environment — flourish in places where other plants cannot survive. Their survival is threatened by "cactus rustlers" who steal these plants for the profitable landscaping trade. Some individuals destroy cactus by operating vehicles off the road while still others use these ancient plants for target practice. It is illegal to disturb or remove cactus on any public lands. By protecting the cactus, you are helping preserve the desert's intricate and fragile web of life.

The text in the above section about cactus/succulents is by Jeri Zemon, State Park Ranger.

Prickly pear cactus

Most prickly pear cactus have yellow, red or purple flowers, even among the same species. They vary in height from less than a foot (plains, hedgehog, tuberous) to 6 or 7 feet (Texas, Santa Rita, pancake). Pads can vary in width, length, shape and color. The beavertail, Santa Rita and blind pear are regarded as spineless, but all have glochids. Like other cactus, most prickly pears and chollas have large spines — actually modified leaves — growing from tubercules, small, wart-like projections on their stems. But members of the Opuntia genus are unique because of their clusters of fine, tiny, barbed spines called glochids. Found just above the cluster of regular spines, glochids are yellow or red in color and detach easily from the pads. Glochids are often difficult to see and more difficult to remove, once lodged in the skin.

Cochineal — an insect — is present in much of the lower elevations in the western United States and Mexico. It feeds almost solely on the pads of selected prickly pear cacti species.

The prickly pear plant (also called nopal or nopalitos in Spanish) and the prickly pear cactus fruit (also known as tuna in Spanish) is an edible nutritious and delicious food offering vitamins, minerals and medicinal properties.

There has been medical interest in the prickly pear plant. Some studies have shown that the pectin contained in the prickly pear pulp lowers levels of "bad" cholesterol while leaving "good" cholesterol levels unchanged. Another study found that the fibrous pectin in the fruit may lower diabetics' need for insulin. Both fruits and pads of the prickly pear cactus are rich in slowly absorbed soluble fibers that help keep blood sugar stable.

Prickly pear extract has also been shown to reduce the severity and occurrence of hangovers if taken in advance of drinking. Nausea, dry mouth, appetite loss and alcohol-related inflammation were all reduced in test subjects who ingested prickly pear extract five hours prior to drinking. (Source: Jeff Wiese; Steve McPherson; Michelle C. Odden; Michael G. Shlipak, “Effect of Opuntia ficus indica on Symptoms of the Alcohol Hangover,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Jun 2004; 164: 1334 - 1340.)

Prickly pear products include everything from prickly pear syrup for deserts, drinks and coolers to cactus candy, jelly and honey!

Cholla cactus

Cholla cactus represent more than 20 species of the Opuntia genus in the North American deserts. Cholla is a term applied to various shrubby cacti of this genus with cylindrical stems composed of segmented joints. These stems are actually modified branches that serve several functions — water storage, photosynthesis and flower production.

Like most cactus, chollas have tubercules — small, wart-like projections on the stems — from which sharp spines, actually modified leaves, grow. But chollas are the only cactus with papery sheaths covering their spines. These sheaths are often bright and colorful, providing the cactus with its distinctive appearance.

Cholla cactus are found in all the hot deserts of the American Southwest, with different species having adapted to different locale and elevation ranges. Most require coarse, well-drained soil in dry, rocky flats or slopes. Some have adapted to mountain forests, while others require steep, rocky slopes in mountain foothills. Most cholla cactus have orange or greenish-yellow flowers with a variety of colors, even among the same species. Most species bloom April through June, depending on local conditions. Stems and joints vary in width, length, shape and color, as well as in the profusion of spines and glochids. Chollas may appear as ground creepers, shrubs or trees, varying in height from less than a foot (club or devil cholla) to as much as 15 feet (chain-fruit cholla).

Saguro cactus

The saguaro cactus is composed of a tall, thick, fluted, columnar stem, 18 to 24 inches in diameter, often with several large branches (arms) curving upward in the most distinctive conformation of all Southwestern cacti.

The skin is smooth and waxy, and the trunk and stems have stout, two-inch spines clustered on their ribs. When water is absorbed, the outer pulp of the saguaro can expand like an accordion, increasing the diameter of the stem and — in this way — can increase its weight by up to a ton.

The saguaro often begins life in the shelter of a "nurse" tree or shrub which can provide a shaded, moist habitat for the germination of life. The saguaro grows very slowly — perhaps an inch a year — but to a great height, 15 to 50 feet. The largest plants, with more than five arms, are estimated to be 200 years old. The average old saguaro has five arms and is about 30 feet tall.

The saguaro has a surprisingly shallow root system, considering its great height and weight. It is supported by a tap root that is only a pad about three feet long, as well as numerous stout roots no deeper than a foot, emanating radially from its base. More smaller roots run radially to a distance equal to the height of the saguaro. These roots wrap about rocks providing anchorage from winds across the rocky bajadas.

Creamy-white, three-inch wide flowers with yellow centers bloom May and June. Clustered near the ends of branches, the blossoms open during cooler desert nights and close again by the next midday. The saguaro flower is the state flower of Arizona.

The slow growth and great capacity of the saguaro to store water allows it to flower every year, regardless of rainfall. The night-blooming flowers have many creamy-white petals around a tube about four inches long. Like most cactus, the buds appear on the southeastern exposure of stem tips, and flowers may completely encircle stems in a good year.

A dense group of yellow stamens forms a circle at the top of the tube; the saguaro has more stamens per flower than any other desert cactus. A sweet nectar accumulates in the bottom of this tube. The saguaro can only be fertilized by cross-pollination — pollen from a different cactus. The sweet nectar, together with the color of the flower, attracts birds, bats and insects, which in acquiring the nectar, pollinate the saguaro flower.

Unlike the Queen of the Night cactus, not all of the flowers on a single saguaro bloom at the same time. Instead, over a period of a month or more, only a few of the up to 200 flowers open each night, secreting nectar into their tubes, and awaiting pollination. These flowers close about noon the following day, never to open again. If fertilization has occurred, fruit will begin to form immediately.

The three-inch, oval, green fruit ripens just before the fall rainy season, splitting open to reveal the bright-red, pulpy flesh which all desert creatures seem to relish. This fruit was an especially important food source to Native Americans of the region who used the flesh, seeds and juice. Seeds from the saguaro fruit are prolific — as many as 4,000 to a single fruit — probably the largest number per flower of any desert cactus.

While the white-wing dove — whose northern range coincides with range of the saguaro — is one of its primary pollinators, it is the Gila woodpecker and the gilded flicker who can be observed making their home in the saguaro by chiseling out small holes in the trunk.

Desert Flora – Trees, Shrubs and Grasses

Joshua Tree

The Joshua tree, the largest of the yuccas, grows only in the Mojave Desert. Natural stands of this picturesque, spike-leafed evergreen grow nowhere else in the world. Its height varies from 15-40 feet with a diameter of one to three feet. They grow two to three inches a year, take 50 to 60 years to mature and can live 150 years.

Joshua trees — and most other yuccas — rely on the female pronuba moth for pollination. No other animal visiting the blooms transfers the pollen from one flower to another. In fact, the female yucca moth has evolved special organs to collect and distribute the pollen onto the surface of the flower. She lays her eggs in the flowers' ovaries, and when the larvae hatch, they feed on the yucca seeds.

Without the moth's pollination, the Joshua tree could not reproduce, nor could the moth, whose larvae would have no seeds to eat. Although old Joshua trees can sprout new plants from their roots, only the seeds produced in pollinated flowers can scatter far enough to establish a new stand.

Mormon pioneers are said to have named this species "Joshua" tree because it mimicked the Old Testament prophet Joshua waving them — with upraised arms — on toward the promised land. This unique species grows abundantly at Joshua Tree National Park in California.

The Joshua tree has bell-shaped blooms, 1.25 to 1.5 inches large, each with six creamy, yellow-green sepals, crowded into 12- to 18-inch, many-branched clusters with an unpleasant odor. The trees bloom mostly in the spring, although not all of them will flower annually.

The fruit is elliptical and green-brown. Six-celled, 2.5 to 4 inches, and somewhat fleshy, it dries and falls soon after maturity in late spring revealing many flat seeds.

Mesquite tree

During the inevitable droughts and deprivations of desert frontier days, mesquite trees served up the primary food source for caravans and settlers. Mesquite beans became “manna from heaven” for the suffering men of the 1841 Texas Santa Fe Expedition said George W. Kendall (quoted by Ken E. Rogers in “The Magnificent Mesquite”) in his journal. “When our provisions and coffee ran out, the men ate [mesquite beans] in immense quantities and roasted or boiled them!” During the Civil War, when groceries often ran short, mesquite beans served as passable coffee. Mesquite blooms, pollinated by bees, yield a connoisseur’s honey.

Mesquite is the most common shrub/small tree of the desert southwest. Like many members of the legume family, mesquite restores nitrogen to the soil. There are three common species of mesquite: honey mesquite, screwbean mesquite and velvet mesquite.

Mesquite beans, durable enough for years of storage, became the livestock feed of choice when pastureland grasses failed due to drought or overgrazing. They were carried by early freighters, who fed the beans to their draft animals, especially in Mexico.

Although often crooked in shape, mesquite tree branches, stable and durable, filled the need for wood during the construction of Spanish missions, colonial haciendas, ranch houses and fencing. Its wood served artisans in the crafting of furniture, flooring, paneling and sculpture. “Of the tree mesquite,” said Dobie, “there is one kind of yellowish wood and another of a deep reddish hue as beautiful when polished as the richest mahogany.” In some areas, mesquites provide a bountiful harvest of wood for use in fireplaces and barbecue grills.

Mesquites, requiring little water and only low maintenance, have found a place in Southwest xeriscaped gardens and parks. They not only produce beans and blooms that attract wildlife, they provide perches and nesting sites for birds, including hummingbirds.

In the frontier days, according to Dobie, mesquites were used by the Indians and the settlers as a source of many remedies for a host of ailments. Indians and settlers believed tea made from the mesquite root or bark cured diarrhea. Boiled mesquite roots yielded a soothing balm that cured colic and healed flesh wounds. Mesquite leaves, crushed and mixed with water and urine, cured headaches. Mesquite gum preparations soothed ailing eyes, eased a sore throat, cleared up dysentery and relieved headaches.

Medical studies of mesquite and other desert foods say that despite its sweetness, mesquite flour — made by grinding whole pods — "is extremely effective in controlling blood sugar levels" in people with diabetes. The sweetness comes from fructose, which the body can process without insulin. In addition, soluble fibers, such as galactomannin gum, in the seeds and pods slow absorption of nutrients, resulting in a flattened blood sugar curve, unlike the peaks that follow consumption of wheat flour, corn meal and other common staples.

From crown to root tips, mesquites have evolved a number of adaptations especially designed to help assure survival in the desert environment. Their thorns, sharply pointed and strong, challenge browsing by desert herbivores. (“They will not decay in the flesh or gristle as will prickly pear thorns,” Dobie said, “but will last longer than any flesh in which they become imbedded.”) Their leaves, small and wax coated, minimize transpiration (evaporation of the plant’s water into the atmosphere). During extreme drought, the mesquites may shed their leaves to further conserve moisture. Their flowers, fragrant and delicate, attract the insects, especially the bees, necessary for prolific pollination. Their seeds, abundant and protectively coated, may last for decades, serving as seed banks that improve the odds for wide distribution and successful germination.

Most notably, mesquites’ root systems give the plants a competitive botanical edge in the desert landscape. As hosts to nitrogen-fixing bacteria, they help enrich otherwise impoverished desert soils in which the plants and their progeny grow. In lateral reach, they outcompete other plants in the battle for soil moisture. In their taproots’ downward reach, they find subsurface water, sometimes 150 to perhaps 200 feet below the surface. According to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Internet site, “The mesquite’s root system is the deepest documented; a live root was discovered in a copper mine over 160 feet below the surface.”

Comments