I walk by an art gallery with several bronze sculptures outside. The way a sculptor can create movement out of such a solid substance has always seemed like a miracle to me. I have a lot of respect for artists and sculptors who create soaring images that touch our souls out of inanimate materials. How do they do it? How can they envision images full of light and dancing from such inflexible and rigid materials as marble, granite or bronze? It is astounding to me. Perhaps I just don’t possess the imagination of sculptors or artists. But I am very grateful for their fertile creativity. Let’s find out more about what it takes to sculpt in bronze.

Bronze is the most popular metal for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze." It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs and small statuettes and figurines, as well as bronze elements to be fitted to other objects such as furniture. It is often gilded to give gilt-bronze or ormolu, the gilding technique of applying finely ground, high-carat gold-mercury amalgam to an object of bronze.

Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mold. Then, as the bronze cools, it shrinks a little, making it easier to separate from the mold. Its strength and ductility or lack of brittleness is an advantage when figures in action are to be created, especially when compared to various ceramic or stone materials, such as marble sculpture. These qualities allow the creation of extended figures, as in “Jeté, or figures that have small cross sections in their support, such as the equestrian statue of “Richard the Lionheart.”

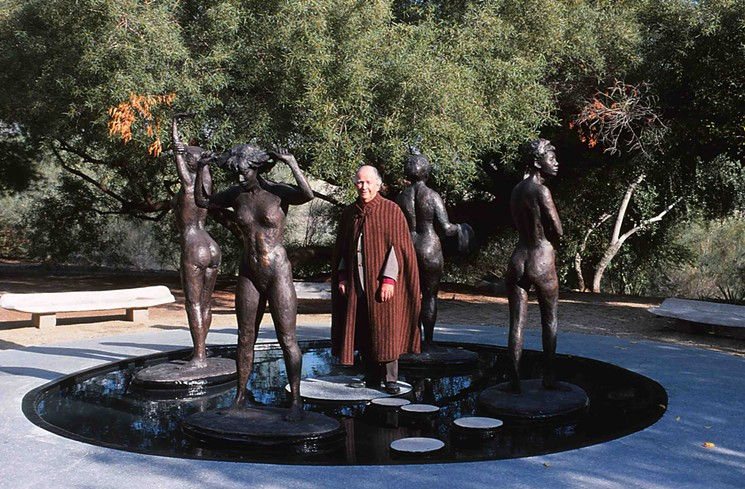

But the value of the bronze for uses other than making statues is disadvantageous to the preservation of sculptures; few large ancient bronzes have survived, as many were melted down to make weapons or ammunition in times of war or to create new sculptures commemorating the victors, while far more stone and ceramic works have come through the centuries, even if only in fragments. As recently as 2007 several life-sized bronze sculptures by John Waddell were stolen, probably due to the value of the metal after the work has been melted. The photo above shows Waddell with his work located at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Paradise Valley.

Material

There are many different bronze alloys, and the term is now tending to be regarded by museums as too imprecise and replaced in descriptions by "copper alloy," especially for older objects. Typically modern bronze is 88% copper and 12% tin. Alpha bronze consists of the alpha solid solution of tin in copper. Alpha bronze alloys of 4–5% tin are used to make coins and a number of mechanical applications. Historical bronzes are highly variable in composition, as most metalworkers probably used whatever scrap was on hand; the metal of the 12th-century English Gloucester Candlestick — an elaborately decorated English Romanesque gilt-bronze candlestick now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London — is bronze containing a mixture of copper, zinc, tin, lead, nickel, iron, antimony, arsenic with an unusually large amount of silver, between 22.5% in the base and 5.76% in the pan below the candle. The proportions of this mixture may suggest that the candlestick was made from a hoard of old coins. The Benin Bronzes are really brass, and the Romanesque Baptismal font at St. Bartholomew’s Church, Liège is described as both bronze and brass.

In the Bronze Age, two forms of bronze were commonly used: "classic bronze," about 10% tin, was used in casting; "mild bronze," about 6% tin, was hammered from ingots to make sheets. Bladed weapons were mostly cast from classic bronze, while helmets and armor were hammered from mild bronze. According to one definition, modern "statuary bronze" is 90% copper and 10% tin.

History

The great civilizations of the old world worked in bronze for art, from the time of the introduction of the alloy for tools and edged weapons. “Dancing Girl” from Mohenjodaro, belonging to the Harappan civilization and dating back to c. 2500 BCE, is perhaps the first known bronze statue. The Greeks were the first to scale the figures up to life size. Few examples exist in good condition; one is the seawater-preserved bronze “Victorious Youth” that required painstaking efforts to bring it to its present state for museum display. Far more Roman bronze statues have survived.

The ancient Chinese knew both lost-wax casting and section mold casting, and during the Shang dynasty created large numbers of Chinese ritual bronzes — ritual vessels covered with complex decoration — which were buried in sets of up to 200 pieces in the tombs of royalty and the nobility. They were produced for an individual or social group to use in making ritual offerings of food and drink to his or their ancestors and other deities or spirits. Such ceremonies generally took place in family temples or ceremonial halls over tombs. These ceremonies can be seen as ritual banquets in which both living and dead members of a family were to supposed participate. Details of these ritual ceremonies are preserved through early literary records. On the death of the owner of a ritual bronze, it would often be placed in his tomb, so that he could continue to pay his respects in the afterlife; other examples were cast specifically as grave goods. Indeed, many surviving examples have been excavated from graves. Over the long creative period of Egyptian dynastic art, small lost-wax bronze figurines were made in large numbers; several thousand of them have been conserved in museum collections.

The 7th-8th century Sri Lankan Sinhalese bronze statue of Buddhist Tara — now in the British Museum — is an excellent example of a bronze statue. Tara is an important figure in Buddhism. She appears as a female bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism, and as a female Buddha in Vajrayana Buddhism. She is known as the "mother of liberation" and represents the virtues of success in work and achievements.

From the ninth through the thirteenth century the Chola dynasty in South India represented the pinnacle of bronze casting in India. They were well known for their art, specifically temple sculptures and “Chola bronzes,” exquisite bronze sculptures of Hindu deities built in a lost wax process they pioneered.

Among the existing specimens in the various museums of the world and in the temples of South India, may be seen many fine figures of Shiva in various forms accompanied by his consort Parvati and the other gods, demigods and goddesses of the Saivaite pantheon, Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, the Nayanmars, other Saiva saints and many more. Though conforming generally to the iconographic conventions established by long tradition, the sculptor could also exercise his imagination within the boundaries of the canonical Hindu iconography and worked in greater freedom during the 11th and the 12th centuries. As a result, the sculptures and bronzes show classic grace, grandeur and taste. The best example of this can be seen in the form of Nataraja, the Divine Dancer.

While the stone sculpture and the inner sanctum image empowering the temple remained immovable, changing religious concepts during the period around the 10th century demanded that the deities take part in a variety of public roles similar to those of a human monarch. As a result, large bronze images were created to be carried outside the temple to participate in daily rituals, processions and temple festivals. The round lugs and holes found on the bases of many of these sculptures are for the poles that were used to carry the heavy images. The deities in bronze who participated in such festivities were sumptuously clothed and decorated with precious jewelery. Their every need and comfort were catered to by a battery of temple priests, musicians, cooks, devadasis, administrators and patrons. The lay public thronged the processional route to have a darshan and admired their beloved deity for the lavish depiction of the figure and the grand costumes and jewelry.

Although bronze casting has a long history in south India, a much larger and a much greater number of bronze sculptures in all sizes ranging from massive to miniature were cast during the Chola period than before, further attesting to the importance of bronze sculpture during this period. When in worship, these images are bedecked in silk costumes, garlands and gem-encrusted jewels, befitting the particular avatar and religious context. Decorating temple bronzes in this way is a tradition at least 1,000 years old and such decorations are referred to in 10th century Chola inscriptions.

In recent times, many of these priceless Chola bronzes have been stolen from their temples or museums, smuggled out of India and have found their way into the private museums of art collectors.

Lost-wax casting

In lost-wax or investment casting, the artist starts with a full-sized model of the sculpture, most often a non-drying, oil-based clay such as Plasticine — putty-like modeling material made from calcium salts, petroleum jelly and aliphatic acids — for smaller sculptures or for sculptures to be developed over an extended period (water-based clays must be protected from drying), and water-based clay for larger sculptures or for sculptures for which it is desired to capture a gestural quality, one that transmits the motion of the sculptor in addition to that of the subject. A mold is made from the clay pattern, either as a piece mold from plaster or using flexible gel or similar rubber-like materials stabilized by a plaster jacket of several pieces. Often a plaster master will be made from this mold for further refinement. Such a plaster is a means of preserving the artwork until a patron may be found to finance a bronze casting, either from the original molds or from a new mold made from the refined plaster positive.

Once a production mold is obtained, a wax — hollow for larger sculptures — is then cast from the mold. For a hollow sculpture, a core is then cast into the void and is retained in its proper location, after wax melting, by pins of the same metal used for casting. A sprue is the vertical passage through which liquid material is introduced into a mold, and it is a large diameter channel through which the material enters the mold. It connects pouring basin to the runner. In many cases it controls the flow of material into the mold. During casting or molding, the material in the sprue will solidify and need to be removed from the finished part. It is usually tapered downwards to minimize turbulence and formation of air bubbles. One or more wax sprues are added to conduct the molten metal into the sculptures — typically directing the liquid metal from a pouring cup to the bottom of the sculpture, which is then filled from the bottom up in order to avoid splashing and turbulence. Additional sprues may be directed upward at intermediate positions, and various vents may also be added where gases could be trapped. (Vents are not needed for ceramic shell casting, allowing the sprue to be simple and direct). The complete wax structure — and core, if previously added — is then invested in another kind of mold or shell, which is heated in a kiln until the wax runs out and all free moisture is removed. The investment is then soon filled with molten bronze. The removal of all wax and moisture prevents the liquid metal from being explosively ejected from the mold by steam and vapor.

Students of bronze casting will usually work in direct wax, where the model is made in wax, possibly formed over a core or with a core cast in place, if the piece is to be hollow. If no mold is made and the casting process fails, the artwork will also be lost. After the metal has cooled, the external ceramic or clay is chipped away, revealing an image of the wax form, including core pins, sprues, vents and risers. All of these are removed with a saw and tool marks are polished away, and interior core material is removed to reduce the likelihood of interior corrosion. Incomplete voids created by gas pockets or investment inclusions are then corrected by welding and carving. Small defects where sprues and vents were attached are filed or ground down and polished.

Creating large sculptures

For a large sculpture, the artist will usually prepare small study models until the pose and proportions are determined. An intermediate-sized model is then constructed with all of the final details. For very large works, this may again be scaled to a larger intermediate. From the final scale model, measuring devices are used to determine the dimensions of an armature for the structural support of a full-size temporary piece, which is brought to rough form by wood, cardboard, plastic foam and/or paper to approximately fill the volume while keeping the weight low. Finally, plaster, clay or other material is used to form the full-size model, from which a mold may be constructed.

Alternatively, a large refractory core may be constructed, and the direct-wax method then applied for subsequent investment. Before modern welding techniques, large sculptures were generally cast in one piece with a single pour. Welding allows a large sculpture to be cast in pieces, then joined.

Finishing

After final polishing, corrosive materials may be applied to form a patina, a process that allows some control over the color and finish.

Another form of sculptural art that uses bronze is ormolu, a finely cast soft bronze that is gilded to produce a matte gold finish. Ormolu was popularized in the 18th century in France and is found in such forms as wall sconces or wall-mounted candle holders, inkstands, clocks and garnitures — collections of any matching, but usually not identical, decorative objects intended to be displayed together. Ormolu wares can be identified by a clear ring when tapped, showing that they are made of bronze — not a cheaper alloy such as spelter (a zinc-lead alloy) or pewter.

The Empire timepiece in the photo above represents Mars and Venus, an allegory of the wedding of Napoleon I and Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria in 1810. It is by the famous bronzier Pierre-Phillipe Thomire, circa 1810.

Benin bronzes

The Benin bronzes are a group of more than 1,000 metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin in what is now modern-day Nigeria. Collectively, the objects form the best-known examples of Benin art, created from the 13th century onwards, by the Edo people, which also included other sculptures in brass or bronze, including some famous portrait heads and smaller pieces.

In 1897 most of the plaques and other objects were looted by British forces during a punitive expedition to the area as imperial control was being consolidated in Southern Nigeria. Two hundred of the pieces were taken to the British Museum, London, while the rest were stolen by other European museums. Today, a large number are held by the British Museum. Other notable collections are in Germany and the USA.

The Benin bronzes led to a greater appreciation in Europe of African culture and art. Initially, it appeared incredible to the discoverers that people "supposedly so primitive and savage" were responsible for such highly developed objects. Some even wrongly concluded that Benin knowledge of metallurgy came from the Portuguese traders who were in contact with Benin in the early modern period. In actual fact, the Benin Empire was a hub of African civilization before the Portuguese traders visited, and it is clear that the bronzes were made in Benin from an indigenous culture. Many of these dramatic sculptures date to the 13th century, centuries before contact with Portuguese traders, and a large part of the collection dates to the 15th and 16th centuries. It is believed that two "golden ages" in Benin metal workmanship occurred during the reigns of Esigie (fl. 1550) and of Ersoyen (1735–50), when their workmanship achieved its highest qualities.

While the collection is known as the Benin bronzes, like most West African "bronzes," the pieces are mostly made of brass of variable composition. There are also pieces made of mixtures of bronze and brass, of wood, of ceramic and of ivory, among other materials.

The metal pieces were made using lost-wax casting and are considered among the best sculptures made using this technique.

Gallery

The Orator, c. 100 BC

Etrusco-Roman bronze statue depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus) Etruscan man wearing a Roman toga while engaged in rhetoric

Statue features an inscription in the Etruscan alphabet

Perseus with the Head of Medusa Benvenuto Cellini, 1545–54

Piazza della Signoria

Florence, Italy

After the statue's cleaning

Grodan (The Frog)

Paris 1889

Per Hasselberg

Cast in bronze 1957

for Rottneros Park near Sunne Värmland/Sweden

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Leone Leoni

Mid-16th century

Brunswick Lion (ca. 1166)

Brunswick, Germany

Prospect Park War Memorial

Augustus Lukeman, 1921

Prospect Park, Brooklyn

Bronze statuette of a horse

Solid cast

Early 5th century BC

Argive workshop

Bronze sculpture in Tbilisi, Georgia

The Spirit of Detroit is a monument with a large bronze statue created by Marshall Fredericks and located at the Coleman A. Young Municipal Center on Woodward Avenue in Detroit, Michigan. Cast in Oslo, Norway, the 26-foot, 9-ton sculpture sits on a 60-ton marble base, and it was the largest cast bronze statue since the Renaissance.

In its left hand, the large, seated figure holds a gilt bronze sphere emanating rays to symbolize God. The people in the figure's right hand are a family group symbolizing all human relationships.

Fredericks did not originally name the sculpture and the name came from the citizens of Detroit based on an inscription from 2 Corinthians (3:17) on the marble wall behind it:

"NOW THE LORD IS THAT SPIRIT AND WHERE THE SPIRIT OF THE LORD IS, THERE IS LIBERTY." II CORINTHIANS 3:17

The 36 x 45 foot semicircular wall includes the seals of the City of Detroit and Wayne County. A plaque in front of the sculpture bears the following inscription: "The artist expresses the concept that God, through the spirit of man, is manifested in the family, the noblest human relationship."

Comments