Monday, March 29, 2021 – Klondike

- Mary Reed

- Apr 7, 2021

- 20 min read

There have been a series of popular commercials since the 1980s with the tagline “What Would You Do for a Klondike Bar?” featuring non-actors and actors alike performing various impressions, dangerous stunts, etc. just for a Klondike ice cream bar. I will have to admit it is a very tasty treat but am not sure it is any better than any other ice cream bar. It is named after the Klondike River in the Yukon territory in Canada, which evokes images of icy freshness. I took a bus tour through western Canada and found the crisp, clean air invigorating and the scenery spectacular. I can see why this region of the country was chosen to promote a “healthy,” delicious snack. Let’s find out more about the bar and the Klondike region.

According to Wikipedia, the Klondike bar was created by the Isaly Dairy Co. of Mansfield, Ohio in the early 1920s and named after the Klondike River of Yukon, Canada. Rights to the name were eventually sold to Good Humor-Breyers Corp., a division of Unilever PLC.

The first recorded advertisement for the Klondike was on February 5, 1922, in the Youngstown Vindicator. The bars are generally wrapped with a silver-colored wrapper depicting a polar bear mascot for the brand. Unlike a traditional frozen ice pop or traditional ice cream bar, the Klondike bar does not have a stick due to its size — a point often touted in advertising.

In 1976, Henry Clarke, owner of Clabir Corp., purchased the rights to the Klondike bar, which had been manufactured and sold by the Isaly's restaurant chain since the 1930s. Clarke introduced Klondike bars to consumers throughout the United States during the 1980s. Under him, sales of the Klondike bar increased from $800,000 annually at the time of the 1976 acquisition by Clabir to more than $60 million.

In 1986, the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals prohibited Kraft Foods Group Inc. from using a wrapper resembling the distinctive Klondike bar wrapper — its "trade dress" — for Kraft's "Polar B'ar" brand ice cream bars. The following year, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of the lower court ruling. In 1988, Kraft settled a trademark dispute with Ambrit Inc. — as the former Isaly Co. Inc. was then known — for $8.5 million.

Klondike River The Klondike River is a tributary of the Yukon River in Canada that gave its name to the Klondike Gold Rush. The Klondike River has its source in the Ogilvie Mountains and flows into the Yukon River at Dawson City. Its name comes from the Hän word Tr’ondëk meaning hammerstone, a tool which was used to hammer down stakes used to set salmon nets. Gold was discovered in tributaries of the Klondike River in 1896, which started the Klondike Gold Rush and is still being mined today.

In Jack London's story "A Relic of the Pliocene” in Collier’s Weekly in 1901, this river was mentioned as "Reindeer River."

Klondike, Yukon Territory, Canada The Klondike is a region of the Yukon territory in northwest Canada, east of the Alaskan border. The area is merely a geographic region and has no function to the territory as any kind of administrative region. The Klondike is famed due to the Klondike Gold Rush, which started in 1896 and lasted until 1899. Gold has been mined continuously in that area, except for a pause in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The name "Klondike" evolved from the Hän word Tr’ondëk. Early gold seekers found it difficult to pronounce the First Nations — largest group of Canadian indigenous people — word, so "Klondike" was the result of this poor pronunciation. The climate is warm in the short summer and very cold during the long winter. By late October, ice will have formed over the rivers. For the majority of the year, the ground is frozen to a depth of 3 to 10 feet.

Klondike Gold Rush The Klondike Gold Rush was a migration by an estimated 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region of the Yukon in northwestern Canada between 1896 and 1899. Gold was discovered there by local miners on August 16, 1896; when news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, it triggered a stampede of prospectors. Some became wealthy, but the majority went in vain. It has been immortalized in films, literature and photographs. To reach the gold fields, most prospectors took the route through the ports of Dyea and Skagway in southeast Alaska. Here, the "Klondikers" could follow either the Chilkoot or the White Pass trails to the Yukon River and sail down to the Klondike. The Canadian authorities required each of them to bring a year's supply of food, in order to prevent starvation. In all, the Klondikers' equipment weighed close to a ton which most carried themselves, in stages. Performing this task and contending with the mountainous terrain and cold climate meant those who persisted did not arrive until summer 1898. Once there, they found few opportunities, and many left disappointed.

To accommodate the prospectors, boom towns sprang up along the routes. At their terminus, Dawson City was founded at the confluence of the Klondike and the Yukon Rivers. From a population of 500 in 1896, the town grew to house approximately 30,000 people by summer 1898. Built of wood, isolated and unsanitary, Dawson suffered from fires, high prices and epidemics. Despite this, the wealthiest prospectors spent extravagantly, gambling and drinking in the salons. The native Hän people, on the other hand, suffered from the rush; they were forcibly moved into a reserve to make way for the Klondikers, and many died. Beginning in 1898, the newspapers that had encouraged so many to travel to the Klondike lost interest in it. In the summer of 1899, gold was discovered around Nome in west Alaska, and many prospectors left the Klondike for the new goldfields, marking the end of the Klondike Gold Rush. The boom towns declined, and the population of Dawson City fell. Gold mining production in the Klondike peaked in 1903 after heavier equipment was brought in. Since then, the Klondike has been mined on and off, and today the legacy draws tourists to the region and contributes to its prosperity.

Background

The indigenous people in northwest America had traded in copper nuggets prior to European expansion. Most of the tribes were aware that gold existed in the region, but the metal was not valued by them. The Russians and the Hudson’s Bay Co. had both explored the Yukon in the first half of the 19th century, but ignored the rumors of gold in favor of fur trading, which offered more immediate profits.

In the second half of the 19th century, American prospectors began to spread into the area. Making deals with the Native Tlingit and Tagish tribes, the early prospectors opened the important routes of Chilkoot and White Pass and reached the Yukon valley between 1870 and 1890. Here, they encountered the Hän people, semi-nomadic hunters and fishermen who lived along the Yukon and Klondike Rivers. The Hän did not appear to know about the extent of the gold deposits in the region.

In 1883, Ed Schieffelin identified gold deposits along the Yukon River, and an expedition up the Fortymile River in 1886 discovered considerable amounts of it and founded Fortymile City. That same year gold had been found on the banks of the Klondike River, but in small amounts and with no claims being made. By the late 1880s, several hundred miners were working their way along the Yukon valley, living in small mining camps and trading with the Hän. On the Alaskan side of the border, Circle City, a logtown, was established in 1893 on the Yukon River. In three years, it grew to become "the Paris of Alaska," with 1,200 inhabitants, saloons, opera houses, schools and libraries. In 1896, it was so well-known that a correspondent from the Chicago Daily Record came to visit. At the end of the year, it became a ghost town, when large gold deposits were found upstream on the Klondike.

Gold discovery in 1896

On August 16, 1896, an American prospector named George Carmack, his Tagish wife Kate Carmack — born Shaaw Tláa, her brother Skookum Jim Mason and their nephew Dawson Charlie (K̲áa Goox̱) were traveling south of the Klondike River. Following a suggestion from Robert Henderson, a Canadian prospector, they began looking for gold on Bonanza Creek, then called Rabbit Creek, one of the Klondike's tributaries. It is not clear who discovered the gold — George Carmack or Skookum Jim — but the group agreed to let George Carmack appear as the official discoverer because they feared that authorities would not

recognize an indigenous claimant.

In any event, gold was present along the river in huge quantities. Carmack measured out four claims — strips of ground that could later be legally mined by the owner, along the river. These included two for himself — one as his normal claim, the second as a reward for having discovered the gold — and one each for Jim and Charlie. The claims were registered the next day at the police post at the mouth of the Fortymile River, and news spread rapidly from there to other mining camps in the Yukon River valley.

By the end of August, all of Bonanza Creek had been claimed by miners. A prospector then advanced up into one of the creeks feeding into Bonanza, later to be named Eldorado Creek. He discovered new sources of gold there, which would prove to be even richer than those on Bonanza. Claims began to be sold between miners and speculators for considerable sums. Just before Christmas, word of the gold reached Circle City. Despite the winter, many prospectors immediately left for the Klondike by dogsled, eager to reach the region before the best claims were taken. The outside world was still largely unaware of the news, and although Canadian officials had managed to send a message to their superiors in Ottawa about the finds and influx of prospectors, the government did not give it much attention. The winter prevented river traffic, and it was not until June 1897 that the first boats left the area, carrying the freshly mined gold and the full story of the discoveries.

Beginning of the stampede –

July 1897 In the resulting Klondike stampede, an estimated 100,000 people tried to reach the Klondike goldfields, of whom only around 30,000 to 40,000 eventually did. It formed the height of the Klondike Gold rush from the summer of 1897 until the summer of 1898. It began on July 15, 1897, in San Francisco and was spurred further two days later in Seattle, when the first of the early prospectors returned from the Klondike, bringing with them large amounts of gold on the ships Excelsior and Portland. The press reported that a total of $1,139,000 — equivalent to $1 billion at 2010 prices — had been brought in by these ships, although this proved to be an underestimate. The migration of prospectors caught so much attention that it was joined by outfitters, writers and photographers.

Various factors lay behind this sudden mass response. Economically, the news had reached the U.S. at the height of a series of financial recessions and bank failures in the 1890s. The gold standard of the time tied paper money to the production of gold, and shortages towards the end of the 19th century meant that gold dollars were rapidly increasing in value ahead of paper currencies and being hoarded. This had contributed to the Panic of 1893 and Panic of 1896, which caused unemployment and financial uncertainty. There was a huge, unresolved demand for gold across the developed world that the Klondike promised to fulfill and, for individuals, the region promised higher wages or financial security.

Psychologically, the Klondike, as historian Pierre Berton describes, was "just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible." Furthermore, the Pacific ports closest to the gold strikes were desperate to encourage trade and travel to the region. The mass journalism of the period promoted the event and the human interest stories that lay behind it. A worldwide publicity campaign engineered largely by Erastus Brainerd, a Seattle newspaperman, helped establish that city as the premier supply center and the departure point for the gold fields.

The prospectors came from many nations, although an estimated majority of 60 to 80% were Americans or recent immigrants to America. Most had no experience in the mining industry, being clerks or salesmen. Mass resignations of staff to join the gold rush became notorious. In Seattle, this included the mayor, twelve policemen and a significant percentage of the city's streetcar drivers.

Some stampeders were famous: John McGraw, the former governor of Washington, joined, together with the prominent lawyer and sportsman A. Balliot. Frederick Burnham, a well-known American scout and explorer, arrived from Africa, only to be called back to take part in the Second Boer War. Among those who documented the rush was the Swedish-born photographer Eric Hegg, who took some of the iconic pictures of Chilkoot Pass, and reporter Tappan Adney, who afterwards wrote a firsthand history of the stampede. Jack London, later a famous American writer, left to seek for gold but made his money during the rush mostly by working for prospectors.

Seattle and San Francisco competed fiercely for business during the rush, with Seattle winning the larger share of trade. Indeed, one of the first to join the gold rush was William D. Wood, the mayor of Seattle, who resigned and formed a company to transport prospectors to the Klondike. The publicity around the gold rush led to a flurry of branded goods being put onto the market. Clothing, equipment, food and medicines were all sold as "Klondike" goods, allegedly designed for the Northwest. Guidebooks were published, giving advice about routes, equipment, mining and capital necessary for the enterprise. The newspapers of the time termed this phenomenon "Klondicitis."

Routes to the Klondike The Klondike could be reached only by the Yukon River, either upstream from its delta, downstream from its head or from somewhere in the middle through its tributaries. Riverboats could navigate the Yukon in the summer from the delta until a point called Whitehorse, above the Klondike. Travel, in general, was made difficult by both geography and climate. The region was mountainous, the rivers winding and sometimes impassable; the short summers could be hot, while from October to June, during the long winters, temperatures could drop below −58 °F. Aids for the travelers to carry their supplies varied; some had brought dogs, horses, mules or oxen, whereas others had to rely on carrying their equipment on their backs or on sleds pulled by hand. Shortly after the stampede began in 1897, the Canadian authorities had introduced rules requiring anyone entering Yukon Territory to bring with them a year's supply of food; typically this weighed around 1,150 pounds. By the time camping equipment, tools and other essentials were included, a typical traveler was transporting as much as a ton in weight. Unsurprisingly, the price of draft animals soared; at Dyea, even poor-quality horses could sell for as much as $700 ($19,000) or be rented out for $40 ($1,100) a day. From Seattle or San Francisco, prospectors could travel by sea up the coast to the ports of Alaska. The route following the coast is now referred to as the Inside Passage. It led to the ports of Dyea and Skagway plus ports of nearby trails. The sudden increase in demand encouraged a range of vessels to be pressed into service including old paddle wheelers, fishing boats, barges and coal ships still full of coal dust. All were overloaded and many sank.

All water routes It was possible to sail all the way to the Klondike, first from Seattle across the northern Pacific to the Alaskan coast. From St. Michael, at the Yukon River delta, a riverboat could then take the prospectors the rest of the way up the river to Dawson, often guided by one of the Native Koyukon people who lived near St. Michael. Although this all-water route, also called "the rich man's route," was expensive and long — 4,700 miles in total — it had the attraction of speed and avoiding overland travel. At the beginning of the stampede, a ticket could be bought for $150 ($4,050) while during the winter 1897–98 the fare settled at $1,000 ($27,000). In 1897, some 1,800 travelers attempted this route, but the vast majority were caught along the river when the region iced over in October. Only 43 reached the Klondike before winter, and of those 35 had to return, having thrown away their equipment en route to reach their destination in time. The remainder mostly found themselves stranded in isolated camps and settlements along the ice-covered river often in desperate circumstances.

Dyea/Skagway routes Most of the prospectors landed at the southeast Alaskan towns of Dyea and Skagway, both located at the head of the natural Lynn Canal at the end of the Inside Passage. From there, they needed to travel over the mountain ranges into Canada's Yukon Territory, and then down the river network to the Klondike. Along the trails, tent camps sprung up at places where prospectors had to stop to eat or sleep or at obstacles such as the icy lakes at the head of the Yukon. At the start of the rush, a ticket from Seattle to the port of Dyea cost $40 ($1,100) for a cabin. Premiums of $100 ($2,700), however, were soon paid, and the steamship companies hesitated to post their rates in advance since they could increase on a daily basis.

White Pass trail

Those who landed at Skagway made their way over the White Pass before cutting across to Bennett Lake. Although the trail began gently, it progressed over several mountains with paths as narrow as two feet and in wider parts covered with boulders and sharp rocks. Under these conditions horses died in huge numbers, giving the route the informal name of Dead Horse Trail. The volumes of travelers and the wet weather made the trail impassable and, by late 1897, it was closed until further notice, leaving around 5,000 stranded in Skagway.

An alternative toll road suitable for wagons was eventually constructed, and it — combined with colder weather that froze the muddy ground — allowed the White Pass to reopen. Prospectors began to make their way into Canada. Moving supplies and equipment over the pass had to be done in stages. Most divided their belongings into 65-pound packages that could be carried on a man's back or heavier loads that could be pulled by hand on a sled. Ferrying packages forwards and walking back for more, prospectors would need about 30 round trips — a distance of at least 2,500 miles — before they had moved all of their supplies to the end of the trail. Even using a heavy sled, a strong man would be covering 1,000 miles and need around 90 days to reach Bennett Lake.

Chilkoot Pass Those who landed at Dyea, Skagway's neighboring town, traveled the Chilkoot Trail and crossed its pass to reach Lake Lindeman, which fed into Lake Bennett at the head of the Yukon River. The Chilkoot Pass was higher than the White Pass, but more used it: around 22,000 during the gold rush. The trail passed up through camps until it reached a flat ledge, just before the main ascent, which was too steep for animals. This location was known as the Scales, and was where goods were weighed before travelers officially entered Canada. The cold, the steepness and the weight of equipment made the climb extremely arduous, and it could take a day to get to the top of the 1,000 feet-high slope. As on the White Pass trail, supplies needed to be broken down into smaller packages and carried in relay. Packers, prepared to carry supplies for cash, were available along the route but would charge up to $1 ($27) per pound on the later stages; many of these packers were natives: Tlingits or, less commonly, Tagish. Avalanches were common in the mountains and, on April 3, 1898, one claimed the lives of more than 60 people traveling over Chilkoot Pass. Entrepreneurs began to provide solutions as the winter progressed. Steps were cut into the ice at the Chilkoot Pass which could be used for a daily fee, this 1,500-step staircase becoming known as the "Golden Steps." By December 1897, Archie Burns built a tramway up the final parts of the Chilkoot Pass. A horse at the bottom turned a wheel, which pulled a rope running to the top and back; freight was loaded on sledges pulled by the rope. Five more tramways soon followed, one powered by a steam engine, charging between 8 and 30 cents ($2 and $8) per pound. An aerial tramway was built in the spring of 1898, able to move 9 tons of goods an hour up to the summit.

Mining Of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people who reached Dawson City during the gold rush, only around 15,000 to 20,000 finally became prospectors. Of these, no more than 4,000 struck gold and only a few hundred became rich. By the time most of the stampeders arrived in 1898, the best creeks had all been claimed, either by the long-term miners in the region or by the first arrivals of the year before. The Bonanza, Eldorado, Hunker and Dominion Creeks were all taken, with almost 10,000 claims recorded by the authorities by July 1898; a new prospector would have to look further afield to find a claim of his own. Geologically, the region was permeated with veins of gold, forced to the surface by volcanic action and then worn away by the action of rivers and streams, leaving nuggets and gold dust in deposits known as placer gold. Some ores lay along the creek beds in lines of soil, typically 15 to 30 feet beneath the surface. Others, formed by even older streams, lay along the hilltops; these deposits were called "bench gold." Finding the gold was challenging. Initially, miners had assumed that all the gold would be along the existing creeks, and it was not until late in 1897 that the hilltops began to be mined. Gold was also unevenly distributed in the areas where it was found, which made the prediction of good mining sites even more uncertain. The only way to be certain that gold was present was to conduct exploratory digging.

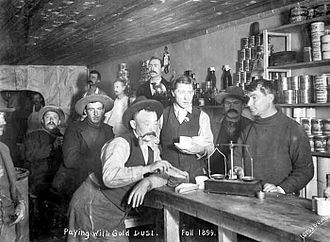

Methods Mining began with clearing the ground of vegetation and debris. Prospect holes were then dug in an attempt to find the ore or "pay streak." If these holes looked productive, proper digging could commence, aiming down to the bedrock, where the majority of the gold was found. The digging would be carefully monitored in case the operation needed to be shifted to allow for changes in the flow. In the sub-Arctic climate of the Klondike, a layer of hard permafrost lay only 6 feet below the surface. Traditionally, this had meant that mining in the region only occurred during the summer months, but the pressure of the gold rush made such a delay unacceptable. Late 19th century technology existed for dealing with this problem, including hydraulic mining and stripping, and dredging, but the heavy equipment required for this could not be brought into the Klondike during the gold rush. Instead, the miners relied on wood fires to soften the ground to a depth of about 14 inches and then removing the resulting gravel. The process was repeated until the gold was reached. In theory, no support of the shaft was necessary because of the permafrost although in practice sometimes the fire melted the permafrost and caused collapses. Fires could also produce noxious gases, which had to be removed by bellows or other tools. The resulting "dirt" brought out of the mines froze quickly in winter and could be processed only during the warmer summer months. An alternative, more efficient, approach called steam thawing was devised between 1897 and 1898; this used a furnace to pump steam directly into the ground, but since it required additional equipment it was not a widespread technique during the years of the rush. In the summer, water would be used to sluice and pan the dirt, separating out the heavier gold from gravel. This required miners to construct sluices, which were sequences of wooden boxes 15 feet long, through which the dirt would be washed; up to 20 of these might be needed for each mining operation. The sluices, in turn, required much water, usually produced by creating a dam and ditches or crude pipes. "Bench gold" mining on the hillsides could not use sluice lines because water could not be pumped that high up. Instead, these mines used rockers, boxes that moved back and forth like a cradle, to create the motion needed for separation. Finally, the resulting gold dust could be exported out of the Klondike; exchanged for paper money at the rate of $16 ($430) per troy ounce through one of the major banks that opened in Dawson City, or simply used as money when dealing with local traders.

Conspicuous consumption The huge quantities of gold coming through Dawson City encouraged a lavish lifestyle among the richer prospectors. Saloons were typically open 24 hours a day, with whiskey the standard drink. Gambling was popular, with the major saloons each running their own rooms; a culture of high stakes evolved, with rich prospectors routinely betting $1,000 ($28,000) at dice or playing for a $5,000 ($140,000) poker pot. The establishments around Front Street had grand facades in a Parisian style, mirrors and plate-glass windows and, from late 1898, were lit by electric light. The dance halls in Dawson were particularly prestigious and major status symbols, both for customers and their owners. Wealthy prospectors were expected to drink champagne at $60 ($1,660) a bottle, and the Pavilion dancehall cost its owner, Charlie Kimball, as much as $100,000 ($2,800,000) to construct and decorate. Elaborate opera houses were built, bringing singers and specialty acts to Dawson. Tales abounded of prospectors spending huge sums on entertainment — Jimmy McMahon once spent $28,000 ($784,000) in a single evening, for example. Most payments were made in gold dust, and in places like saloons, there was so much spilled gold that a profit could be made just by sweeping the floor. Some of the richest prospectors lived flamboyantly in Dawson. Swiftwater Bill Gates, a gambler and ladies' man who rarely went anywhere without wearing silk and diamonds, was one of them. To impress a woman who liked eggs — then an expensive luxury — he was alleged to have bought all the eggs in Dawson, had them boiled and fed them to dogs. Another miner, Frank Conrad, threw a sequence of gold objects onto the ship as tokens of his esteem when his favorite singer left Dawson City. The wealthiest dancehall girls followed suit: Daisy D'Avara had a belt made for herself from $340 ($9,520) in gold dollar coins; another, Gertie Lovejoy, had a diamond inserted between her two front teeth. The miner and businessman Alex McDonald, despite being styled the "King of the Klondike," was unusual among his peers for his lack of grandiose spending.

Role of women In 1898 8% of those living in the Klondike territory were women, and in towns like Dawson this rose to 12%. Many women arrived with their husbands or families, but others travelled alone. Most came to the Klondike for similar economic and social reasons as male prospectors, but they attracted particular media interest. The gender imbalance in the Klondike encouraged business proposals to ship young, single women into the region to marry newly wealthy miners; few, if any, of these marriages ever took place, but some single women appear to have traveled on their own in the hope of finding prosperous husbands. Guidebooks gave recommendations for what practical clothes women should take to the Klondike: the female dress code of the time was formal, emphasizing long skirts and corsets, but most women adapted this for the conditions of the trails. Regardless of experience, women in a party were typically expected to cook for the group. Few mothers brought their children with them due to the risks of the travel.

Once in the Klondike, very few women—less than 1%—actually worked as miners. Many were married to miners; however, their lives as partners on the gold fields were still hard and often lonely. They had extensive domestic duties, including thawing ice and snow for water, breaking up frozen food, chopping wood and collecting wild foods. In Dawson and other towns, some women took in laundry to make money. This was a physically demanding job but could be relatively easily combined with child care duties. Others took jobs in the service industry, for example as waitresses or seamstresses, which could pay well, but were often punctuated by periods of unemployment. Both men and women opened roadhouses, but women were considered to be better at running them. A few women worked in the packing trade, carrying goods on their backs or became domestic servants.

Wealthier women with capital might invest in mines and other businesses. One of the most prominent businesswomen in the Klondike was Belinda Mulrooney. She brought a consignment of cloth and hot water bottles with her when she arrived in the Klondike in early 1897, and with the proceeds of those sales she first built a roadhouse at Grand Forks and later a grand hotel in Dawson. She invested widely, including acquiring her own mining company, and was reputed to be the richest woman of the Klondike. The wealthy Martha Black was abandoned by her husband early in the journey to the Klondike but continued on without him, reaching Dawson City where she became a prominent citizen, investing in various mining and business ventures with her brother.

A relatively small number of women worked in the entertainment and sex industries. The elite of these women were the highly paid actresses and courtesans of Dawson; beneath them were chorus line dancers, who usually doubled as hostesses and other dance hall workers. While still better paid than white-collar male workers, these women worked very long hours and had significant expenses. The entertainment industry merged into the sex industry, where women made a living as prostitutes. The sex industry in the Klondike was concentrated in Klondike City and in a backstreet area of Dawson.A hierarchy of sexual employment existed, with brothels and parlor houses at the top, small independent "cigar shops" in the middle and at the bottom, the prostitutes who worked out of small huts called "hutches." Life for these workers was a continual struggle, and the suicide rate was high.

The degree of involvement between Indigenous women and the stampeders varied. Many Tlingit women worked as packers for the prospectors, for example, carrying supplies and equipment, sometimes also transporting their babies as well. Hän women had relatively little contact with the white immigrants, however, and there was a significant social divide between local Hän women and white women. Although before 1897 there had been a number of Indigenous women who married western men, including Kate Carmack, the Tagish wife of one of the discoverers, this practice did not survive into the stampede. Very few stampeders married Hän women, and very few Hän women worked as prostitutes. "Respectable" white women would avoid associating with Indigenous women or prostitutes: those that did could cause scandal.

Comments