Monday, January 17, 2022 – Martin Luther King Jr.

- Mary Reed

- Jan 18, 2022

- 37 min read

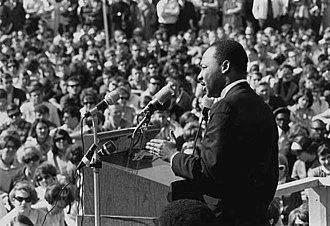

Happy Martin Luther King Jr. Day! He had a profound influence on all of our lives and is definitely the “king” of peaceful protest. He could not be more of a contrast the to the white supremacy of Birmingham, Alabama Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor. He knew how to make the world see where there was injustice. And he did it with nonviolence and civil disobedience. And eloquence — oh my what a silver tongue he had! His speeches were legendary and really did help even white people to see his point of view, the argument for basic civil rights for those of color. Let’s learn more about him.

Martin Luther King Jr. — born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968 — was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesman and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. Renamed after German reformer Martin Luther, he advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist and minister Martin Luther King Sr.

King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights. He led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or SCLC. As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. He helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic standoffs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent. Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.

On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. In 1965, he helped organize two of the three Selma to Montgomery marches. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards poverty, capitalism and the Vietnam War. In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. His death was followed by riots in many U.S. cities. Allegations that James Earl Ray, the man convicted of killing King, had been framed or acted in concert with government agents persisted for decades after the shooting. King was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2003. Martin Luther King Jr. Day was established as a holiday in cities and states throughout the United States beginning in 1971; the holiday was enacted at the federal level by legislation signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. Hundreds of streets in the U.S. have been renamed in his honor, and the most populous county in Washington State was rededicated for him. The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

Birth

King was born Michael King Jr. on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, the second of three children to Michael King and Alberta King (née Williams). King had an older sister, Christine King Farris, and a younger brother, Alfred Daniel "A.D." King. King's maternal grandfather Adam Daniel Williams, who was a minister in rural Georgia, moved to Atlanta in 1893, and became pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in the following year. Williams was of African-Irish descent. Williams married Jennie Celeste Parks. King Sr. was born to sharecroppers, James Albert and Delia King of Stockbridge, Georgia. In his adolescent years, King Sr. left his parents' farm and walked to Atlanta where he attained a high school education and enrolled in Morehouse College to study for entry to the ministry. King Sr. and Alberta began dating in 1920 and married on November 25, 1926. Until Jennie's death in 1941, they lived together on the second floor of her parent's two-story Victorian house, where King was born.

Shortly after marrying Alberta, King Sr. became assistant pastor of the Ebenezer church. Senior pastor Williams died in the spring of 1931 and that fall, King Sr. took the role, where he would in time raise the attendance from 600 to several thousand. In 1934, the church sent King Sr. on a multinational trip to Rome, Tunisia, Egypt, Jerusalem, Bethlehem then Berlin for the meeting of the Baptist World Alliance or BWA. The trip also included visits to sites in Germany associated with the Reformation leader, Martin Luther. While there, King Sr. witnessed the rise of Nazism. In reaction, the BWA conference issued a resolution that stated, "This Congress deplores and condemns as a violation of the law of God the Heavenly Father, all racial animosity, and every form of oppression or unfair discrimination toward the Jews, toward colored people, or toward subject races in any part of the world." He returned home in August 1934, and at that time changed his name to Martin Luther King and his son's to Martin Luther King Jr.

Early childhood

At his childhood home, King and his two siblings would read aloud the Bible as instructed by their father. After dinners there, King's grandmother Jennie, who he affectionately referred to as "Mama," would tell lively stories from the Bible to her grandchildren. King's father would regularly use whippings to discipline his children. At times, King Sr. would also have his children whip each other. King's father later remarked, "[King] was the most peculiar child whenever you whipped him. He'd stand there, and the tears would run down, and he'd never cry." Once when King witnessed his brother A.D. emotionally upset his sister Christine, he took a telephone and knocked out A.D. with it. When he and his brother were playing at their home, A.D. slid from a banister and hit into their grandmother, Jennie, causing her to fall down unresponsive. King, believing her dead, blamed himself and attempted suicide by jumping from a second-story window. Upon hearing that his grandmother was alive, King rose and left the ground where he had fallen.

King became friends with a white boy whose father owned a business across the street from his family's home. In September 1935, when the boys were about six years old, they started school. King had to attend a school for black children, Younge Street Elementary School, while his close playmate went to a separate school for white children only. Soon afterwards, the parents of the white boy stopped allowing King to play with their son, stating to him "we are white, and you are colored." When King relayed the happenings to his parents, they had a long discussion with him about the history of slavery and racism in America. Upon learning of the hatred, violence and oppression that black people had faced in the U.S., King would later state that he was "determined to hate every white person." His parents instructed him that it was his Christian duty to love everyone.

King witnessed his father stand up against segregation and various forms of discrimination. Once, when stopped by a police officer who referred to King Sr. as "boy," King's father responded sharply that King was a boy but he was a man. When King's father took him into a shoe store in downtown Atlanta, the clerk told them they needed to sit in the back. King's father refused, stating "we'll either buy shoes sitting here or we won't buy any shoes at all," before taking King and leaving the store. He told King afterward, "I don't care how long I have to live with this system, I will never accept it." In 1936, King's father led hundreds of African Americans in a civil rights march to the city hall in Atlanta, to protest voting rights discrimination. King later remarked that King Sr. was "a real father" to him.

King memorized and sang hymns, and stated verses from the Bible, by the time he was five years old. Over the next year, he began to go to church events with his mother and sing hymns while she played piano. His favorite hymn to sing was "I Want to Be More and More Like Jesus;" he moved attendees with his singing. King later became a member of the junior choir in his church. King enjoyed opera and played the piano. As he grew up, King garnered a large vocabulary from reading dictionaries and consistently used his expanding lexicon. He got into physical altercations with boys in his neighborhood, but oftentimes used his knowledge of words to stymie fights. King showed a lack of interest in grammar and spelling, a trait that he carried throughout his life. In 1939, King sang as a member of his church choir in slave costume, for the all-white audience at the Atlanta premiere of the film “Gone with the Wind.” In September 1940, at the age of 11, King was enrolled at the Atlanta University Laboratory School for the seventh grade. While there, King took violin and piano lessons and showed keen interest in his history and English classes.

On May 18, 1941, when King had sneaked away from studying at home to watch a parade, he was informed that something had happened to his maternal grandmother. Upon returning home, he found out that she had suffered a heart attack and died while being transported to a hospital. He took the death very hard and believed that his deception of going to see the parade may have been responsible for God taking her. King jumped out of a second-story window at his home, but again survived an attempt to kill himself. His father instructed him in his bedroom that King should not blame himself for her death, and that she had been called home to God as part of God's plan that could not be changed. King struggled with this and could not fully believe that his parents knew where his grandmother had gone. Shortly thereafter, King's father decided to move the family to a two-story brick home on a hill that overlooked downtown Atlanta.

Adolescence

In his adolescent years, he initially felt resentment against whites due to the "racial humiliation" that he, his family and his neighbors often had to endure in the segregated South. In 1942, when King was 13 years old, he became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal. That year, King skipped the ninth grade and was enrolled in Booker T. Washington High School, where he maintained a B-plus average. The high school was the only one in the city for African American students. It had been formed after local black leaders, including King's grandfather (Williams), urged the city government of Atlanta to create it.

While King was brought up in a Baptist home, he grew skeptical of some of Christianity's claims as he entered adolescence. He began to question the literalist teachings preached at his father's church. At the age of 13, he denied the bodily resurrection of Jesus during Sunday school. He said that he found himself unable to identify with the emotional displays and gestures from congregants frequent at his church and doubted if he would ever attain personal satisfaction from religion. He later stated of this point in his life, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly."

In high school, King became known for his public speaking ability, with a voice that had grown into an orotund baritone. He proceeded to join the school's debate team. He continued to be most drawn to history and English and chose English and sociology to be his main subjects while at the school. King maintained an abundant vocabulary. But, he relied on his sister, Christine, to help him with his spelling, while King assisted her with math. They studied in this manner routinely until Christine's graduation from high school. He also developed an interest in fashion — commonly adorning himself in well-polished patent leather shoes and tweed suits — which gained him the nickname "Tweed" or "Tweedie" among his friends. He further grew a liking for flirting with girls and dancing. His brother A. D. later remarked, "He kept flitting from chick to chick, and I decided I couldn't keep up with him. Especially since he was crazy about dances and just about the best jitterbug in town."

On April 13, 1944, in his junior year, King gave his first public speech during an oratorical contest, sponsored by the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World in Dublin, Georgia. In his speech he stated, "black America still wears chains. The finest negro is at the mercy of the meanest white man. Even winners of our highest honors face the class color bar." He was selected as the winner of the contest. On the ride home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so that white passengers could sit down. The driver of the bus called King a "black son-of-a-bitch." He initially refused but complied after his teacher told him that he would be breaking the law if he did not follow the directions of the driver. As all the seats were occupied, he and his teacher were forced to stand on the rest of the drive back to Atlanta. Later he wrote of the incident, saying "That night will never leave my memory. It was the angriest I have ever been in my life."

Morehouse College

During King's junior year in high school, Morehouse College — an all-male historically black college that King's father and maternal grandfather had attended — began accepting high school juniors who passed the school's entrance examination. As World War II was underway, many black college students had been enlisted in the war, decreasing the numbers of students at Morehouse College. So, the university aimed to increase their student numbers by allowing junior high school students to apply. In 1944, at the age of 15, King passed the entrance examination and was enrolled at the university for the school season that autumn.

In the summer before King started his freshman year at Morehouse, he boarded a train with his friend — Emmett "Weasel" Proctor — and a group of other Morehouse College students to work in Simsbury, Connecticut at the tobacco farm of Cullman Brothers Tobacco, a cigar business. This was his first trip outside of the segregated South into the integrated north. In a June 1944 letter to his father King wrote about the differences that struck him between the two parts of the country, "On our way here we saw some things I had never anticipated to see. After we passed Washington there was no discrimination at all. The white people here are very nice. We go to any place we want to and sit anywhere we want to." The students worked at the farm to be able to provide for their educational costs at Morehouse College, as the farm had partnered with the college to allot their salaries towards the university's tuition, housing and other fees. On weekdays King and the other students worked in the fields, picking tobacco from 7:00 am till at least 5:00 pm, enduring temperatures above 100°F, to earn roughly $4 per day. On Friday evenings, he and the other students visited downtown Simsbury to get milkshakes and watch movies, and on Saturdays they would travel to Hartford, Connecticut to see theatre performances, shop and eat in restaurants. On each Sunday they would go to Hartford to attend church services, at a church filled with white congregants. King wrote to his parents about the lack of segregation in Connecticut, relaying how he was amazed they could go to "one of the finest restaurants in Hartford" and that "Negroes and whites go to the same church."

He played freshman football there. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, the 18-year-old King chose to enter the ministry. Throughout his time in college, King studied under the mentorship of its president, Baptist minister Benjamin Mays, who he would later credit with being his "spiritual mentor." He had concluded that the church offered the most assuring way to answer "an inner urge to serve humanity." His "inner urge" had begun developing, and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a "rational" minister with sermons that were "a respectful force for ideas, even social protest." He graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts in sociology in 1948, at age 19.

Crozer Theological Seminary

King enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania. King's father fully supported his decision to continue his education and made arrangements for King to work with prominent Crozer alum, J. Pius Barbour, a family friend who pastored at Calvary Baptist Church in nearby Chester, Pennsylvania. King became known as one of the "Sons of Calvary," an honor he shared with William Augustus Jones Jr. and Samuel D. Proctor who both went on to become well-known preachers in the black church.

While attending Crozer, King was joined by Walter McCall, a former classmate at Morehouse. At Crozer, King was elected president of the student body. The African American students of Crozer for the most part conducted their social activity on Edwards Street. King became fond of the street because a classmate had an aunt who prepared collard greens for them, which they both relished.

King once reproved another student for keeping beer in his room, saying they had shared responsibility as African Americans to bear "the burdens of the Negro race." For a time, he was interested in Walter Rauschenbusch's "social gospel." In his third year at Crozer, King became romantically involved with the white daughter of an immigrant German woman who worked as a cook in the cafeteria. The woman had been involved with a professor prior to her relationship with King. He planned to marry her, but friends advised against it, saying that an interracial marriage would provoke animosity from both blacks and whites, potentially damaging his chances of ever pastoring a church in the South. He tearfully told a friend that he could not endure his mother's pain over the marriage and broke the relationship off six months later. He continued to have lingering feelings toward the woman he left; one friend was quoted as saying, "He never recovered." He graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951.

Boston University

In 1951, King began doctoral studies in systematic theology at Boston University. While pursuing doctoral studies, King worked as an assistant minister at Boston's historic Twelfth Baptist Church with William Hunter Hester. Hester was an old friend of King's father and was an important influence on King. In Boston, he befriended a small cadre of local ministers his age and sometimes guest pastored at their churches — including Michael Haynes, associate pastor at Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury and younger brother of jazz drummer Roy Haynes. The young men often held bull sessions in their various apartments, discussing theology, sermon style and social issues.

King attended philosophy classes at Harvard University as an audit student in 1952 and 1953.

At the age of 25 in 1954, King was called as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. He received his Ph.D. degree on June 5, 1955, with a dissertation — initially supervised by Edgar S. Brightman and, upon the latter's death, by Lotan Harold DeWolf — titled “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.”

An academic inquiry in October 1991 concluded that portions of his doctoral dissertation had been plagiarized, and he had acted improperly. However, "[d]espite its finding, the committee said that 'no thought should be given to the revocation of Dr. King's doctoral degree,' an action that the panel said would serve no purpose." The committee found that the dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." A letter is now attached to the copy of King's dissertation held in the university library, noting that numerous passages were included without the appropriate quotations and citations of sources. Significant debate exists on how to interpret King's plagiarism.

Marriage and family

While studying at Boston University, he asked a friend from Atlanta named Mary Powell — who was a student at the New England Conservatory of Music — if she knew any nice Southern girls. Powell asked fellow student Coretta Scott if she was interested in meeting a Southern friend studying divinity. Scott was not interested in dating preachers but eventually agreed to allow Martin to telephone her based on Powell's description and vouching. On their first phone call, King told Scott "I am like Napoleon at Waterloo before your charms," to which she replied, "You haven't even met me." They went out for dates in his green Chevy. After the second date, King was certain Scott possessed the qualities he sought in a wife. She had been an activist at Antioch in undergrad, where Carol and Rod Serling were schoolmates.

King married Coretta Scott on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama. They became the parents of four children: Yolanda King (1955–2007), Martin Luther King III (b. 1957), Dexter Scott King (b. 1961) and Bernice King (b. 1963). During their marriage, King limited Coretta's role in the civil rights movement, expecting her to be a housewife and mother.

In December 1959, after being based in Montgomery for five years, King announced his return to Atlanta at the request of the SCLC. In Atlanta, he served until his death as co-pastor with his father at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and helped expand the civil rights movement across the South.

In March 1955, Claudette Colvin — a 15-year-old black schoolgirl in Montgomery — refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in violation of Jim Crow laws, local laws in the Southern United States that enforced racial segregation. King was on the committee from the Birmingham African American community that looked into the case; E. D. Nixon and Clifford Durr decided to wait for a better case to pursue because the incident involved a minor.

Nine months later on December 1, 1955, a similar incident occurred when Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. The two incidents led to the Montgomery bus boycott, which was urged and planned by Nixon and led by King. He was in his 20s and had just taken up his clerical role. The other ministers asked him to take a leadership role simply because his relative newness to community leadership made it easier for him to speak out. King was hesitant about taking the role but decided to do so if no one else wanted the role.

The boycott lasted for 385 days, and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed. He was arrested and jailed during this campaign, which overnight drew the attention of national media and greatly increased King's public stature. The controversy ended when the United States District Court issued a ruling in Browder v. Gayle that prohibited racial segregation on all Montgomery public buses. Blacks resumed riding the buses again, and were able to sit in the front with full legal authorization.

King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

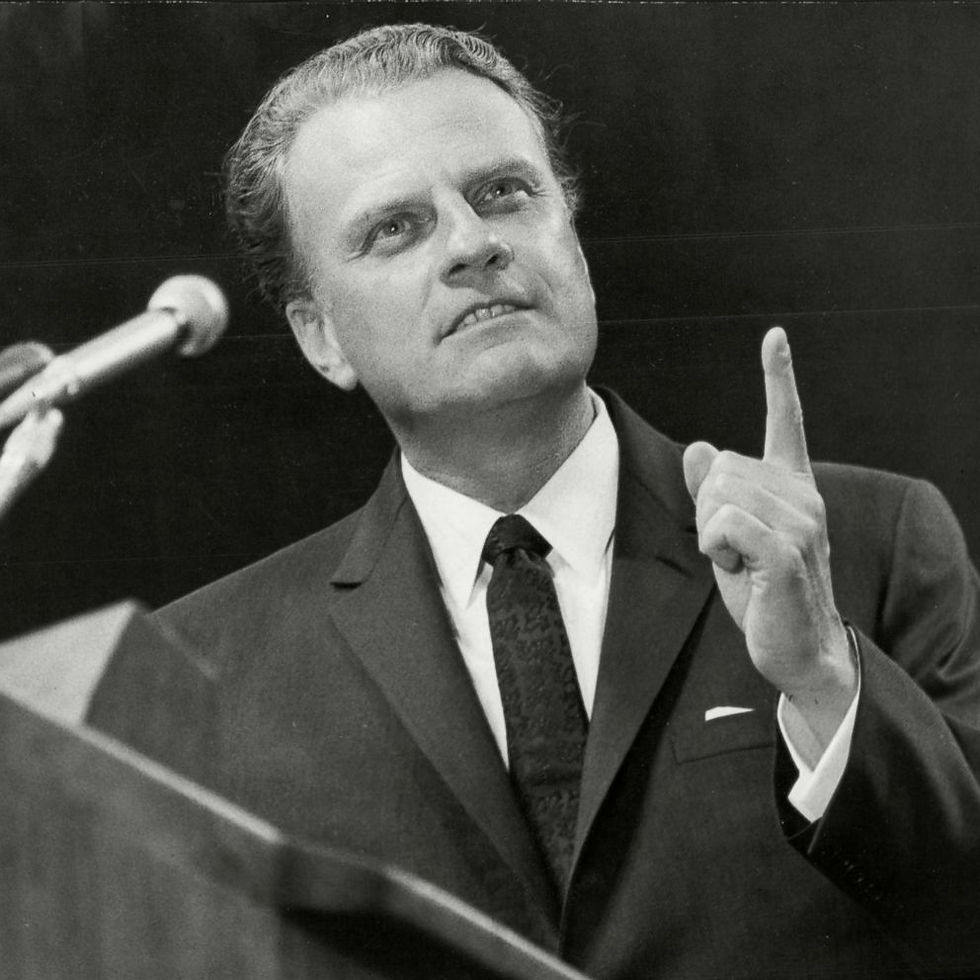

In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or SCLC. The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. The group was inspired by the crusades of evangelist Billy Graham, who befriended King, as well as the national organizing of the group In Friendship, founded by King allies Stanley Levison and Ella Baker. King led the SCLC until his death. The SCLC's 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was the first time King addressed a national audience. Other civil rights leaders involved in the SCLC with King included: James Bevel, Allen Johnson, Curtis W. Harris, Walter E. Fauntroy, C. T. Vivian, Andrew Young, The Freedom Singers, Cleveland Robinson, Randolph Blackwell, Annie Bell Robinson Devine, Charles Kenzie Steele, Alfred Daniel Williams King, Benjamin Hooks, Aaron Henry and Bayard Rustin.

The Common Society

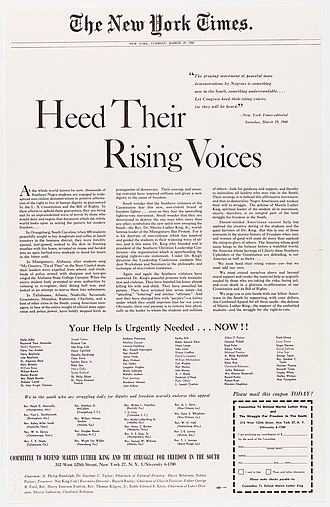

Harry Wachtel joined King's legal advisor Clarence B. Jones in defending four ministers of the SCLC in the libel case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan; the case was litigated in reference to the newspaper advertisement "Heed Their Rising Voices." Wachtel founded a tax-exempt fund to cover the suit's expenses and assist the nonviolent civil rights movement through a more effective means of fundraising. This organization was named the "Gandhi Society for Human Rights." King served as honorary president for the group. He was displeased with the pace that President Kennedy was using to address the issue of segregation. In 1962, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document that called on the President to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and issue an executive order to deliver a blow for civil rights as a kind of Second Emancipation Proclamation. Kennedy did not execute the order.

The FBI was underwriting a directive from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy when it began tapping King's telephone line in the fall of 1963. Kennedy was concerned that public allegations of communists in the SCLC would derail the administration's civil rights initiatives. He warned King to discontinue these associations and later felt compelled to issue the written directive that authorized the FBI to wiretap King and other SCLC leaders. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover feared the civil rights movement and investigated the allegations of communist infiltration. When no evidence emerged to support this, the FBI used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years in attempts to force King out of his leadership position in the COINTELPRO program, a series of covert and illegal projects conducted by the FBI aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting and disrupting domestic American political organizations.

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks — along with segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers — produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced the majority of Americans that the civil rights movement was the most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into the law of the United States with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic standoffs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.

Survived knife attack 1958

On September 20, 1958, King was signing copies of his book “Stride Toward Freedom” in Blumstein's department store in Harlem when he narrowly escaped death. Izola Curry — a mentally ill black woman who thought that King was conspiring against her with communists — stabbed him in the chest with a letter opener, which nearly impinged on the aorta. King received first aid by police officers Al Howard and Philip Romano. King underwent emergency surgery with three doctors — Aubre de Lambert Maynard, Emil Naclerio and John W. V. Cordice. He remained hospitalized for several weeks. Curry was later found mentally incompetent to stand trial.

Atlanta sit-ins, prison sentence and the 1960 elections

Georgia governor Ernest Vandiver expressed open hostility towards King's return to his hometown in late 1959. He claimed that "wherever M. L. King, Jr. has been there has followed in his wake a wave of crimes" and vowed to keep King under surveillance. On May 4, 1960, several months after his return, King drove writer Lillian Smith to Emory University when police stopped them. King was cited for "driving without a license" because he had not yet been issued a Georgia license. King's Alabama license was still valid, and Georgia law did not mandate any time limit for issuing a local license. King paid a fine but was apparently unaware that his lawyer agreed to a plea deal that also included a probationary sentence.

Meanwhile, the Atlanta Student Movement had been acting to desegregate businesses and public spaces in the city, organizing the Atlanta sit-ins from March 1960 onwards. In August the movement asked King to participate in a mass October sit-in, timed to highlight how 1960's presidential election campaign had ignored civil rights. The coordinated day of action took place on October 19. King participated in a sit-in at the restaurant inside Rich's, Atlanta's largest department store, and was among the many arrested that day. The authorities released everyone over the next few days, except for King. Invoking his probationary plea deal, Judge J. Oscar Mitchell sentenced King on October 25 to four months of hard labor. Before dawn the next day, King was taken from his county jail cell and transported to a maximum-security state prison.

The arrest and harsh sentence drew nationwide attention. Many feared for King's safety, as he started a prison sentence with people convicted of violent crimes, many of them white and hostile to his activism. Both presidential candidates were asked to weigh in, at a time when both parties were courting the support of Southern whites and their political leadership including Governor Vandiver. Nixon, with whom King had a closer relationship prior to the sit-in, declined to make a statement despite a personal visit from Jackie Robinson requesting his intervention. Nixon's opponent John F. Kennedy called the governor — a Democrat — directly, enlisted his brother Robert to exert more pressure on state authorities and also, at the personal request of Sargent Shriver, made a phone call to King's wife to express his sympathy and offer his help. The pressure from Kennedy and others proved effective, and King was released two days later. King's father decided to openly endorse Kennedy's candidacy for the November 8 election which he narrowly won.

After the October 19 sit-ins and following unrest, a 30-day truce was declared in Atlanta for desegregation negotiations. However, the negotiations failed, and sit-ins and boycotts resumed in full swing for several months. On March 7, 1961, a group of Black elders including King notified student leaders that a deal had been reached: the city's lunch counters would desegregate in fall 1961, in conjunction with the court-mandated desegregation of schools. Many students were disappointed at the compromise. In a large meeting March 10 at Warren Memorial Methodist Church, the audience was hostile and frustrated towards the elders and the compromise. King then gave an impassioned speech calling participants to resist the "cancerous disease of disunity" and helped to calm tensions.

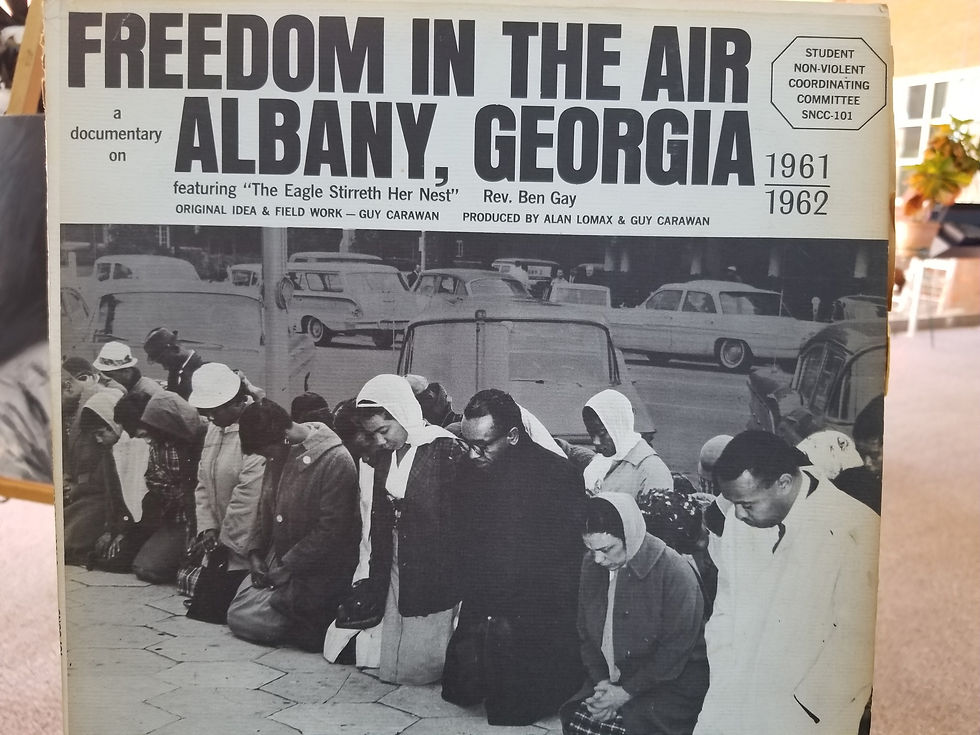

Albany Movement 1961

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. In December, King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel." The following day he was swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. According to King, "that agreement was dishonored and violated by the city" after he left town.

King returned in July 1962 and was given the option of 45 days in jail or a $178 fine — equivalent to $1,500 in 2020 — he chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Police Chief Laurie Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools ... ejected from churches ... and thrown into jail ... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail." It was later acknowledged by the King Center that Billy Graham was the one who bailed King out of jail during this time.

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote nonviolence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts. Though the Albany effort proved a key lesson in tactics for King and the national civil rights movement, the national media was highly critical of King's role in the defeat and the SCLC's lack of results contributed to a growing gulf between the organization and the more radical SNCC. After Albany, King sought to choose engagements for the SCLC in which he could control the circumstances, rather than entering into pre-existing situations.

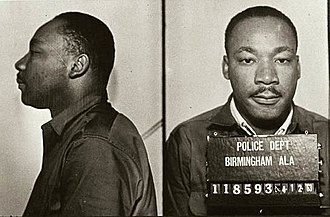

Birmingham campaign 1963

In April 1963, the SCLC began a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. The campaign used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by Wyatt Tee Walker. Black people in Birmingham, organizing with the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating laws that they considered unjust.

King's intent was to provoke mass arrests and "create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation." The campaign's early volunteers did not succeed in shutting down the city or in drawing media attention to the police's actions. Over the concerns of an uncertain King, SCLC strategist James Bevel changed the course of the campaign by recruiting children and young adults to join in the demonstrations. Newsweek called this strategy a Children's Crusade.

During the protests, the Birmingham Police Department, led by Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs against protesters, including children. Footage of the police response was broadcast on national television news and dominated the nation's attention, shocking many white Americans and consolidating black Americans behind the movement. Not all of the demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. But the campaign was a success: Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs came down and public places became more open to blacks. King's reputation improved immensely.

King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign — his 13th arrest out of 29. From his cell, he composed the now-famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail" that responds to calls on the movement to pursue legal channels for social change. The letter has been described as "one of the most important historical documents penned by a modern political prisoner." King argued that the crisis of racism is too urgent, and the current system too entrenched: "We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed." He pointed out that the Boston Tea Party — a celebrated act of rebellion in the American colonies — was illegal civil disobedience and that, conversely, "everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was 'legal.'" Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, arranged for $160,000 to bail out King and his fellow protestors.

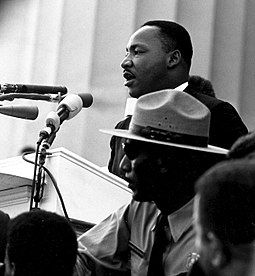

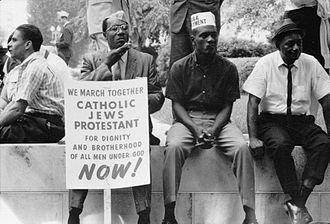

March on Washington 1963

King, representing the SCLC, was among the leaders of the "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on August 28, 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were Roy Wilkins, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James L. Farmer Jr., Congress of Racial Equality.

Bayard Rustin's open homosexuality, support of socialism and his former ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin, which King agreed to do. However, he did collaborate in the 1963 March on Washington, for which Rustin was the primary logistical and strategic organizer. For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of United States President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march.

Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation. However, the organizers were firm that the march would proceed. With the march going forward, the Kennedys decided it was important to work to ensure its success. President Kennedy was concerned the turnout would be less than 100,000. Therefore, he enlisted the aid of additional church leaders and Walter Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers, to help mobilize demonstrators for the cause.

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern U.S. and an opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks. The group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone. As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington" and the Nation of Islam forbade its members from attending the march.

The march made specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public schools, meaningful civil rights legislation including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment, protection of civil rights workers from police brutality, a $2 minimum wage for all workers — equivalent to $17 in 2020 and self-government for Washington, D.C., then governed by congressional committee. Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success. More than a quarter of a million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington, D.C.'s history.

I (We) Have a Dream

King delivered a 17-minute speech, later known as "I Have a Dream." In the speech's most famous passage — in which he departed from his prepared text, possibly at the prompting of Mahalia Jackson, who shouted behind him, "Tell them about the dream!" — King said:

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal." I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification; one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

"I Have a Dream" came to be regarded as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory. The March — and especially King's speech — helped put civil rights at the top of the agenda of reformers in the United States and facilitated passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The original typewritten copy of the speech, including King's handwritten notes on it, was discovered in 1984 to be in the hands of George Raveling, the first African American basketball coach of the University of Iowa. In 1963, Raveling, then 26 years old, was standing near the podium, and immediately after the oration, impulsively asked King if he could have his copy of the speech, and he got it.

Selma voting rights movement and “Bloody Sunday” 1965

In December 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or SNCC in Selma, Alabama, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months. A local judge issued an injunction that barred any gathering of three or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL or any of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965. During the 1965 march to Montgomery, Alabama, violence by state police and others against the peaceful marchers resulted in much publicity, which made racism in Alabama visible nationwide.

Acting on James Bevel's call for a march from Selma to Montgomery, Bevel and other SCLC members, in partial collaboration with SNCC, attempted to organize a march to the state's capital. The first attempt to march on March 7, 1965, at which King was not present, was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has become known as Bloody Sunday and was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the civil rights movement. It was the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King and Bevel's nonviolence strategy.

On March 5, King met with officials in the Johnson Administration in order to request an injunction against any prosecution of the demonstrators. He did not attend the march due to church duties, but he later wrote, "If I had any idea that the state troopers would use the kind of brutality they did, I would have felt compelled to give up my church duties altogether to lead the line." Footage of police brutality against the protesters was broadcast extensively and aroused national public outrage.

King next attempted to organize a march for March 9. The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in federal court against the State of Alabama; this was denied and the judge issued an order blocking the march until after a hearing. Nonetheless, King led marchers on March 9 to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, then held a short prayer session before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement. Meanwhile, on March 11, King cried at the news of Johnson supporting a voting rights bill on television in Marie Foster's living room. The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, 1965. At the conclusion of the march on the steps of the state capitol, King delivered a speech that became known as "How Long, Not Long." In it, King stated that equal rights for African Americans could not be far away, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice" and "you shall reap what you sow."

Opposition to the Vietnam War

King was long opposed to American involvement in the Vietnam War, but at first avoided the topic in public speeches in order to avoid the interference with civil rights goals that criticism of President Johnson's policies might have created. At the urging of SCLC's former Director of Direct Action and now the head of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, James Bevel, and inspired by the outspokenness of Muhammad Ali, King eventually agreed to publicly oppose the war as opposition was growing among the American public.

During an April 4, 1967, appearance at the New York City Riverside Church — exactly one year before his death — King delivered a speech titled "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence." He spoke strongly against the U.S.'s role in the war, arguing that the U.S. was in Vietnam "to occupy it as an American colony" and calling the U.S. government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." He connected the war with economic injustice, arguing that the country needed serious moral change:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries and say: "This is not just."

King opposed the Vietnam War because it took money and resources that could have been spent on social welfare at home. The United States Congress was spending more and more on the military and less and less on anti-poverty programs at the same time. He summed up this aspect by saying, "A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death." He stated that North Vietnam "did not begin to send in any large number of supplies or men until American forces had arrived in the tens of thousands" and accused the U.S. of having killed a million Vietnamese, "mostly children." King also criticized American opposition to North Vietnam's land reforms.

King's opposition cost him significant support among white allies, including President Johnson, Billy Graham, union leaders and powerful publishers. "The press is being stacked against me," King said, complaining of what he described as a double standard that applauded his nonviolence at home, but deplored it when applied "toward little brown Vietnamese children." Life magazine called the speech "demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi," and The Washington Post declared that King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people."

The "Beyond Vietnam" speech reflected King's evolving political advocacy in his later years, which paralleled the teachings of the progressive Highlander Research and Education Center, with which he was affiliated. King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation, and more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice. He guarded his language in public to avoid being linked to communism by his enemies, but in private he sometimes spoke of his support for social democracy and democratic socialism.

In a 1952 letter to Coretta Scott, he said: "I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic ..." In one speech, he stated that "something is wrong with capitalism" and claimed, "There must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism." King had read Marx while at Morehouse, but while he rejected "traditional capitalism," he rejected communism because of its "materialistic interpretation of history" that denied religion, its "ethical relativism" and its "political totalitarianism."

King stated in "Beyond Vietnam" that "true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar ... it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring." He quoted a United States official who said that from Vietnam to Latin America, the country was "on the wrong side of a world revolution." King condemned America's "alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America" and said that the U.S. should support "the shirtless and barefoot people" in the Third World rather than suppressing their attempts at revolution.

King's stance on Vietnam encouraged Allard K. Lowenstein, William Sloane Coffin and Norman Thomas — with the support of anti-war Democrats — to attempt to persuade King to run against President Johnson in the 1968 United States presidential election. King contemplated but, ultimately, decided against the proposal on the grounds that he felt uneasy with politics and considered himself better suited for his morally unambiguous role as an activist.

On April 15, 1967, King participated and spoke at an anti-war march from Manhattan's Central Park to the United Nations. The march was organized by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and initiated by its chairman, James Bevel. At the U.N. King brought up issues of civil rights and the draft:

I have not urged a mechanical fusion of the civil rights and peace movements. There are people who have come to see the moral imperative of equality, but who cannot yet see the moral imperative of world brotherhood. I would like to see the fervor of the civil-rights movement imbued into the peace movement to instill it with greater strength. And I believe everyone has a duty to be in both the civil-rights and peace movements. But for those who presently choose but one, I would hope they will finally come to see the moral roots common to both.

Seeing an opportunity to unite civil rights activists and anti-war activists, Bevel convinced King to become even more active in the anti-war effort. Despite his growing public opposition towards the Vietnam War, King was not fond of the hippie culture which developed from the anti-war movement. In his 1967 Massey Lecture, King stated:

The importance of the hippies is not in their unconventional behavior, but in the fact that hundreds of thousands of young people, in turning to a flight from reality, are expressing a profoundly discrediting view on the society they emerge from.

On January 13, 1968 — the day after President Johnson's State of the Union Address — King called for a large march on Washington against "one of history's most cruel and senseless wars."

We need to make clear in this political year, to congressmen on both sides of the aisle and to the president of the United States, that we will no longer tolerate, we will no longer vote for men who continue to see the killings of Vietnamese and Americans as the best way of advancing the goals of freedom and self-determination in Southeast Asia.

Poor Peoples’ Campaign 1968

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. King traveled the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an "economic bill of rights" for poor Americans.

The campaign was preceded by King's final book, “Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?” which laid out his view of how to address social issues and poverty. King quoted from Henry George and George's book, “Progress and Poverty,” particularly in support of a guaranteed basic income. The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C., demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States.

King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America's cities. He felt that Congress had shown "hostility to the poor" by spending "military funds with alacrity and generosity." He contrasted this with the situation faced by poor Americans, claiming that Congress had merely provided "poverty funds with miserliness." His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of "racism, poverty, militarism and materialism" and argued that "reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced."

The Poor People's Campaign was controversial even within the civil rights movement. Rustin resigned from the march, stating that the goals of the campaign were too broad, that its demands were unrealizable and that he thought that these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.

Assassination

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, in support of the black sanitary public works employees, who were represented by AFSCME Local 1733. The workers had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment. In one incident, black street repairmen received pay for two hours when they were sent home because of bad weather, but white employees were paid for the full day.

On April 3, King addressed a rally and delivered his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" address at Mason Temple, the world headquarters of the Church of God in Christ. King's flight to Memphis had been delayed by a bomb threat against his plane. In the prophetic peroration of the last speech of his life, in reference to the bomb threat, King said the following:

And then I got to Memphis. And some began to say the threats or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers? Well, I don't know what will happen now. We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. So, I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

King was booked in Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel — owned by Walter Bailey — in Memphis. Ralph Abernathy, who was present at the assassination, testified to the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations that King and his entourage stayed at Room 306 so often that it was known as the "King-Abernathy suite." According to Jesse Jackson, who was present, King's last words on the balcony before his assassination were spoken to musician Ben Branch, who was scheduled to perform that night at an event King was attending: "Ben, make sure you play 'Take My Hand, Precious Lord' in the meeting tonight. Play it real pretty."

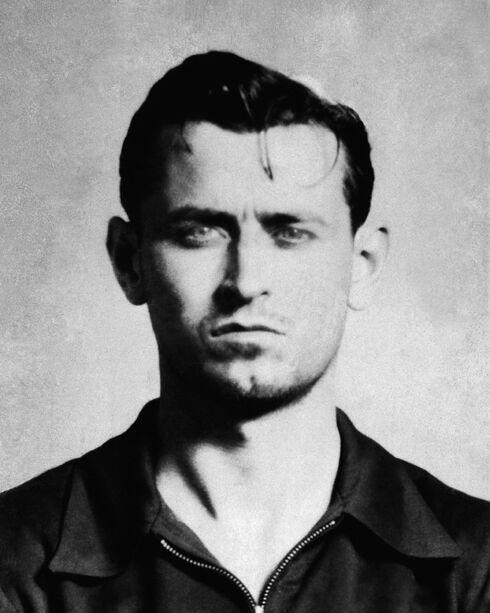

King was fatally shot by James Earl Ray at 6:01 p.m., Thursday, April 4, 1968, as he stood on the motel's second-floor balcony. The bullet entered through his right cheek, smashing his jaw, then traveled down his spinal cord before lodging in his shoulder. Abernathy heard the shot from inside the motel room and ran to the balcony to find King on the floor. Jackson stated after the shooting that he cradled King's head as King lay on the balcony, but this account was disputed by other colleagues of King; Jackson later changed his statement to say that he had "reached out" for King.

After emergency chest surgery, King died at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m. According to biographer Taylor Branch, King's autopsy revealed that though only 39-years-old, he "had the heart of a 60-year-old" which Branch attributed to the stress of 13 years in the civil rights movement. King was initially interred in South View Cemetery in South Atlanta, but in 1977 his remains were transferred to a tomb on the site of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historical Park.

Aftermath

The assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Louisville, Kansas City and dozens of other cities. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis for a campaign rally when he was informed of King's death. He gave a short, improvised speech to the gathering of supporters informing them of the tragedy and urging them to continue King's ideal of nonviolence. The following day, he delivered a prepared response in Cleveland. James Farmer Jr. and other civil rights leaders also called for nonviolent action, while the more militant Stokely Carmichael called for a more forceful response. The city of Memphis quickly settled the strike on terms favorable to the sanitation workers.

The plan to set up a shantytown in Washington, D.C., was carried out soon after the April 4 assassination. Criticism of King's plan was subdued in the wake of his death, and the SCLC received an unprecedented wave of donations for the purpose of carrying it out. The campaign officially began in Memphis on May 2 at the hotel where King was murdered. Thousands of demonstrators arrived on the National Mall and stayed for six weeks, establishing a camp they called "Resurrection City."

President Lyndon B. Johnson tried to quell the riots by making several telephone calls to civil rights leaders, mayors and governors across the United States and told politicians that they should warn the police against the unwarranted use of force. But his efforts didn't work out: "I'm not getting through," Johnson told his aides. "They're all holing up like generals in a dugout getting ready to watch a war." Johnson declared April 7 a national day of mourning for the civil rights leader. Vice President Hubert Humphrey attended King's funeral on behalf of the President, as there were fears that Johnson's presence might incite protests and perhaps violence. At his widow's request, King's last sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church was played at the funeral, a recording of his "Drum Major" sermon, given on February 4, 1968. In that sermon, King made a request that at his funeral no mention of his awards and honors be made, but that it be said that he tried to "feed the hungry," "clothe the naked," "be right on the [Vietnam] war question" and "love and serve humanity." His good friend Mahalia Jackson sang his favorite hymn, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" at the funeral. The assassination helped to spur the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Two months after King's death, James Earl Ray — who was on the loose from a previous prison escape — was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave England on a false Canadian passport. He was using the alias Ramon George Sneyd on his way to white-ruled Rhodesia. Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, though he recanted this confession three days later. On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray pleaded guilty to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty. He was sentenced to a 99-year prison term. Ray later claimed a man he met in Montreal, Quebec with the alias “Raoul” was involved and that the assassination was the result of a conspiracy. He spent the remainder of his life attempting, unsuccessfully, to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had. Ray died in 1998 at age 70.

Comments